Value of luxury

Researchers dig into why global consumers buy luxury goods

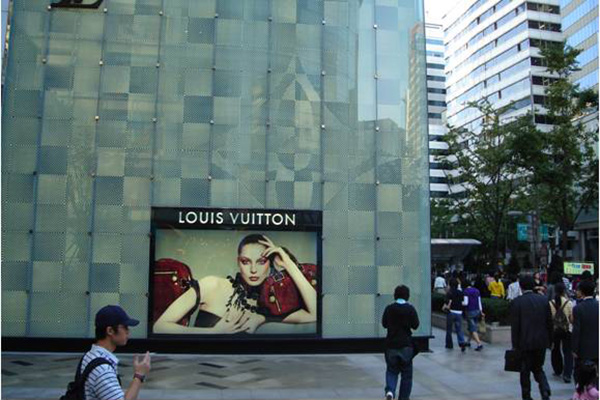

10:13 a.m., Feb. 6, 2013--A young woman in Tokyo pays 243,000 Yen for a Louis Vuitton suitcase emblazoned with the company’s iconic monogram. A continent away, another woman purchases the same suitcase at the company’s store on New York’s 5th Avenue for the equivalent price in dollars, $3,000. Why? What motivates their purchases? And, do those motivations hinge on their location?

That is precisely what University of Delaware researcher Jaehee Jung and her collaborators at universities in nine other countries sought to answer. Their findings published recently in the journal, Psychology & Marketing, compared consumers’ perceptions of luxury.

Research Stories

Chronic wounds

Prof. Heck's legacy

Despite the glum worldwide economy, luxury goods are selling well. Jung, an associate professor of fashion and apparel studies, and the others found that consumers in different countries, like the two women described above, purchase luxury goods for different reasons. For luxury goods makers, it is critical to consider these motivations, Jung said.

In the U.S. it’s about hedonism.

“American consumers generally buy goods for self fulfillment, rather than to please others,” she said.

Jung surveyed American college students. Many responded positively to statements such as “pleasure is all that matters.” Factors including the quality of luxury items were not a driving concern for the students. Jung said this preference isn’t surprising; it is cultural.

“In Western cultures where individualism is valued there is generally less pressure to fit in with groups, such as peers and co-workers, than in Eastern cultures where collectivism is valued,” she said.

Hedonistic tendencies may be creeping into countries with developing economies. Brazilian and Indian students perceived luxury in the same way.

Surveys of students in France indicated they value luxury items because they are expensive and exclusive. French consumers responded positively to statements including: “true luxury products cannot be mass produced” and “few people own a true luxury product.”

“Many luxury goods originate in France,” Jung said. “Cultural heritage and pride might have made them feel luxury is not for everyone.”

Meanwhile Germans focused on function, placing emphasis on quality standards over prestige, as did the Italians, Hungarians and Slovakians.

Jung and her collaborators intend to keep exploring what drives luxury purchases, saying it has consequence for marketers, as demand increases and their target consumer base widens. A growing number of customers, college students included, now have a taste for luxury goods, but are not necessarily financially stable. Still, they buy.

Article by Andrea Boyle Tippett