A sociologist's perspective

Scarpitti details career as criminologist and author for retired faculty

8:35 a.m., Dec. 4, 2012--Frank Scarpitti planned to go to law school but a couple of influential professors at a major Midwest university persuaded him to pursue graduate studies in criminology.

The decision led Scarpitti to a long and distinguished career at the University of Delaware, where the Pennsylvania native authored a watershed report on race relations at the University during the late 1960s.

People Stories

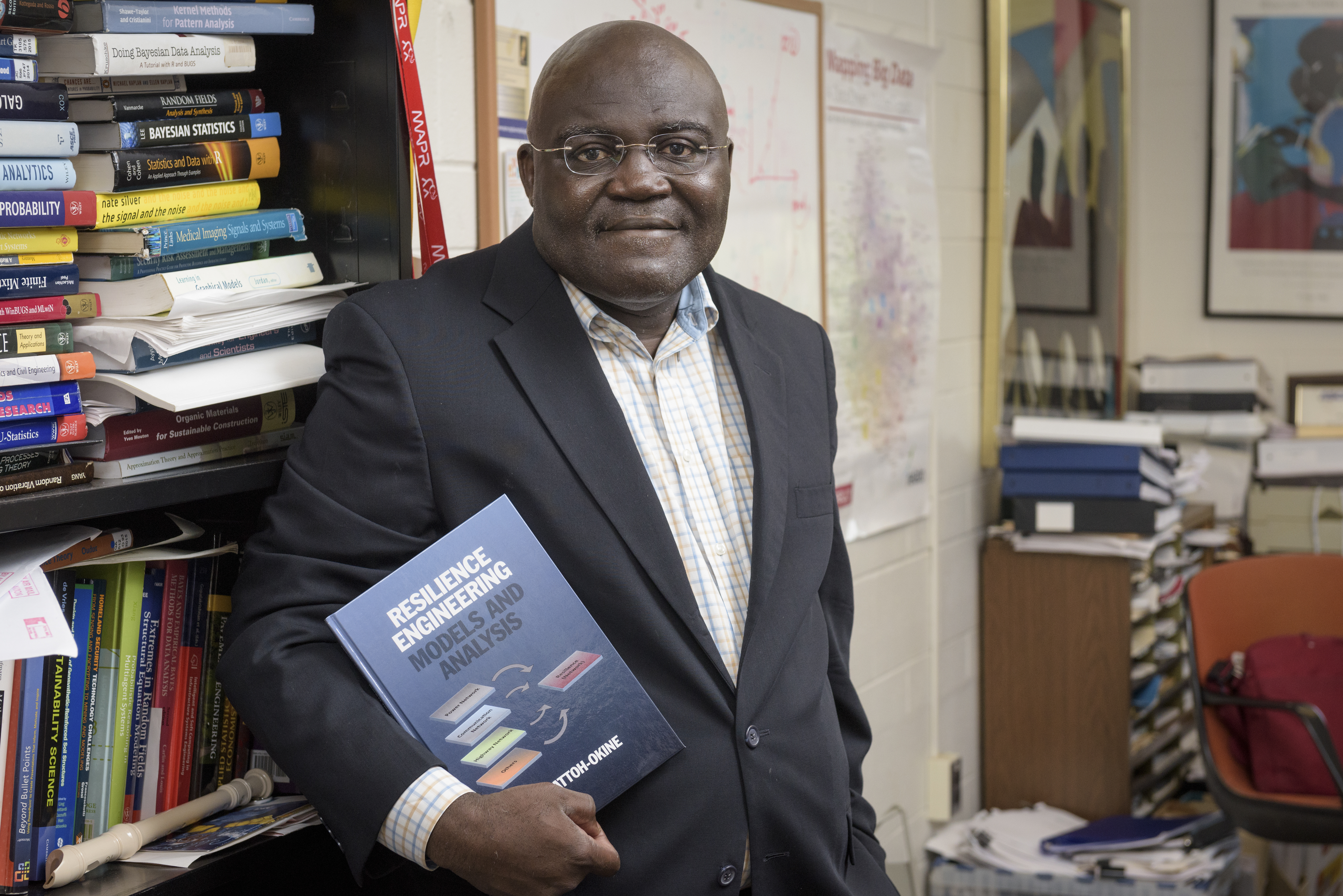

'Resilience Engineering'

Reviresco June run

Scarpitti, the Edward F. and Elizabeth Goodman Rosenberg Professor Emeritus of Sociology, recounted his career as an academic and author during a My Intellectual Journey lecture sponsored by the UD Association of Retired Faculty (UDARF) on Friday, Nov. 30, at the Courtyard Newark-University of Delaware.

“My intellectual journey began in a small mill town in Pennsylvania. My dad was a sickly man and he decided that moving to Florida would be better for his health,” Scarpitti said. “My mother never really liked living there and after two years we moved to Cleveland, Ohio, where I attended Glenville High School.”

It was in high school where Scarpitti was “adopted” by a group of high achieving students, and he sought to emulate them and to compete with them intellectually.

In his senior year at Cleveland State University in 1958, Scarpitti first encountered the writing of Walter C. Reckless, a pioneer in American criminology and corrections.

“His work was something that I really admired, and it was something that I could identify with,” Scarpitti said. “I enjoyed reading the book and I loved the criminological perspective and the theories he was presenting.”

When the chairman of the sociology department at Cleveland State University learned that Scarpitti wanted to go to law school but could not afford it, he suggested an alternative academic path.

“The chairman called me into his office and asked me if I had thought about going to graduate school in sociology. He said, ‘You can get an assistantship or a fellowship,’” Scarpitti said. ”I also thought that if I was going to go to graduate school in sociology, I would to be going to Ohio State University.”

At Ohio State, Scarpitti came under the tutelage of his adviser Simon (Sy) Dinitz, who helped Reckless establish a strong and enduring tradition of criminology there.

After earning his master’s degree and doctorate at Ohio State, Scarpitti was urged by Dinitz, who would become a close personal friend, to take a job as assistant professor at Rutgers University.

“Coming from the Midwest, the East Coast had a kind of glamour, a sort of pizazz -- New York, Philadelphia, Washington -- and Rutgers is right in the middle,” Scarpitti said. “The people I interviewed with told me they believed in giving a young man from the Midwest a chance, so I took the job and had a good four years at Rutgers.”

During a meeting in Chicago during that fourth year, Scarpitti met Frederick B. Parker, chairman of UD’s sociology department, who asked him to join the faculty at UD.

“I didn’t know where Newark, Del., was, but I knew who the Blue Hens were, and that they used to play Rutgers in football and beat them rather consistently,” Scarpitti said. “My wife Ellen and I took a drive down and visited friends in Wilmington. I took the job.”

Another new arrival in the next year, 1968, was recently appointed UD President Edward A. (Art) Trabant, who asked Scarpitti chair a committee charged with making recommendations for improving the conditions of minorities, particularly African Americans, on campus.

The working group, which included African Americans, white students and an Asian American student, met through the winter and presented a report to Trabant in March 1969, which included a host of recommendations.

“We reported that the UD Board of Trustees need to recruit minority students,” Scarpitti said. “We also said that the University should think of itself as a regional institution rather than a state school, in order to have a larger pool of minority students to recruit from.”

Although not all members agreed with what became known as the Scarpitti Report, all of the recommendations were implemented over the next couple of years, including the appointment of an African American scholar, James Newton, and representation on the Board of Trustees, in the administration and on the faculty.

In looking back on a career that includes receiving the Francis Alison Award, UD’s highest faculty honor, Scarpitti, who retired in 2005, said that he is satisfied with the contributions he was able to make.

Since 2006, the Frank Scarpitti Graduate Studies Award has been presented annually to an outstanding graduate student in the Department of Sociology and Criminal Justice.

Comparing science to the building of a pyramid of pebbles, Scarpitti noted that most scientists contribute their individual pebbles, and that, with time, this pile may reach the top where it perhaps answers a question or solves a problem.

“That is the objective. Sometimes, someone comes along and puts a stone or rock on it, but there are not too many Einsteins or Darwins. Most of us put our pebbles there,” Scarpitti said. “I became satisfied with knowing that I put a few pebbles on the pyramid and that I helped to develop the science of criminology and sociology.”

Scarpitti’s talk concluded with a standing ovation by an appreciative audience. A reception followed the lecture.

Article by Jerry Rhodes

Photo by Kathy F. Atkinson