From Nuremberg to now

Expert addresses the divide between biomedical research, clinical practice

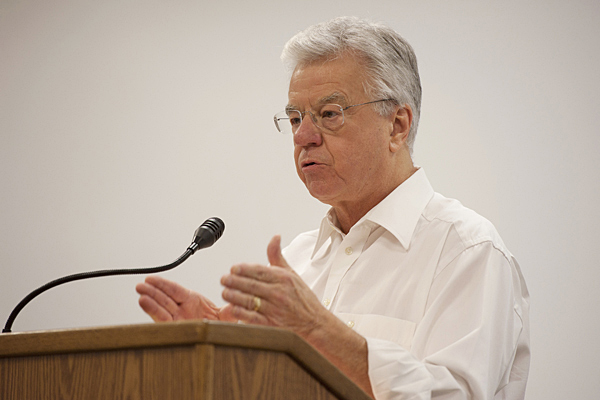

11:35 a.m., Nov. 7, 2011--Nazi atrocities on Jewish prisoners during World War led to creation of the Nuremberg Code in 1947, but, according to research ethics expert Tom Beauchamp, the code did little to stem abuse of human subjects.

“This abnormality in German medicine was sufficiently great to gain our attention, but in terms of how American medicine regulated itself, we basically learned nothing,” said Beauchamp in an invited lecture at the University of Delaware on Thursday, Nov. 2.

Research Stories

Chronic wounds

Prof. Heck's legacy

Beauchamp said that the brutal research protocols of the Nazi experiments—which included protracted immersion in ice water, ingestion of poisons and exposure to viruses—could just as easily have occurred in the United States. “Anti-Semitism was rampant here, too,” he said, “but America was saved by its egalitarian spirit.”

Indeed, the U.S. had its own little shops of research horrors, including Walter Reed’s yellow fever experiments on poor Spanish immigrants and the Tuskegee syphilis studies on black men. Both of these cases, Beauchamp said, exploited vulnerable populations.

It wasn’t until 1966, when the New England Journal of Medicine published a seminal article by Henry Beecher on unethical practices in medical experimentation, that people started to pay attention to what was going on in research labs across the country.

“Beecher basically gathered 20 of the worst experiments that appeared in medical journals and let them speak for themselves,” Beauchamp said. “All of this work had already been published, but no one had complained because it had been presented as a routine part of American medicine.”

Beecher’s paper led to the use of institutional review boards for human subjects research. While Beauchamp did not dispute the value of the changes effected in biomedical research following its publication, he suggested that the end result was a bifurcated system of accepted practice on the one hand and research on the other.

“Federal regulations do not apply to the practice of medicine, while research is heavily regulated,” Beauchamp said. “What this suggests is that the distinction is a mighty one.”

Beauchamp recommended a tighter integration of the two as we move forward in biomedicine. “Imagine a world where research and practice are seamlessly bonded,” he said, “where research drives patient care from diagnosis through treatment and rehabilitation.”

About the speaker

Tom Beauchamp is a professor of philosophy and senior research scholar at Georgetown University’s Kennedy Institute of Ethics. His research interests are in the ethics of human subjects research, the place of universal principles and rights in biomedical ethics, methods of bioethics, Hume and the history of modern philosophy, and business ethics.

In 1975, he joined the staff of the National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research, where he wrote the bulk of The Belmont Report. His publications have also included four major textbooks, a number of edited and coedited anthologies and more than 150 scholarly articles in journals and books.

In 2004, Beauchamp was given the Lifetime Achievement Award of the American Society of Bioethics and Humanities in recognition of outstanding contributions and significant publications in bioethics and the humanities. In 2010, he received the Henry Beecher Award of The Hastings Center for a lifetime of contributions to research ethics.

Article by Diane Kukich

Photos by Kathy F. Atkinson