Sea change

Penguins provide window into shifting Antarctic ecosystem

10:33 a.m., Jan. 18, 2012--What’s the best way to study the Antarctic’s ecosystem? Follow the penguins.

Scientists are tracking penguins on land, under the sea, and even from space to unravel the environmental dynamics in the West Antarctic Peninsula as the region experiences climate change.

Global Stories

Fulbright awards

Peace Corps plans

“We’re not just down there bird watching,” said Matthew Oliver, assistant professor of oceanography in UD’s College of Earth, Ocean, and Environment. “This is a concerted effort to put the whole ecosystem together.”

Rising annual temperatures have had a trickle-down effect around the peninsula, which extends northward from Antarctica toward South America. Warmer conditions have decreased the amount of sea ice present there, as well as potentially the numbers of krill that feed on phytoplankton nearby. Fewer krill means less food for Adélie penguins, and both populations have declined 70 to 80 percent in recent decades.

To better understand what is happening, researchers are studying this food web in relation to physical properties of the ocean. A team from the Polar Oceans Research Group is currently in Antarctica attaching tracking devices to several penguins simultaneously. The penguins then go about their foraging routines, leaving their rookeries to swim out to sea and catch krill.

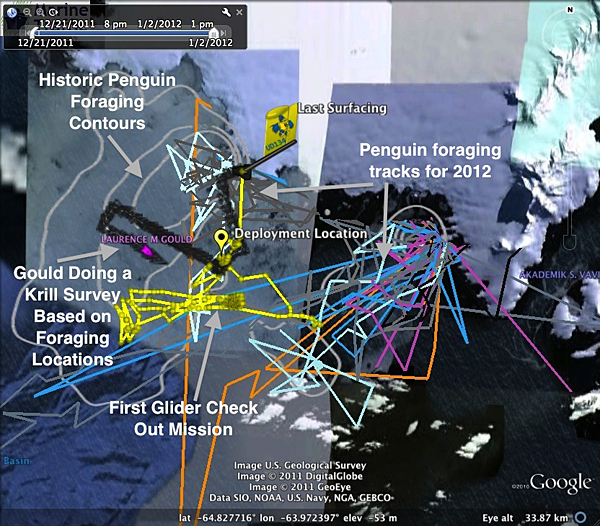

Each evening their pre-programmed tracking devices transmit information via satellite about where they have traveled during the previous 24 hours. Computers at UD receive emails from these penguins that describe their locations, and then they process that data and overlay the individual penguins’ routes in colorful, zig-zagged lines on a specialized map based on Google Earth.

Next the researchers predict where the penguins’ future scavenging patterns will be, taking into account additional information from NASA satellites.

Back in Antarctica, underwater robots called gliders are programmed and sent into the ocean to measure temperature, salinity, chlorophyll and other indicators along the birds’ routes. By analyzing these different factors, the team is trying to figure out which elements influence the penguins’ behavior.

“As we understand where these penguins are foraging, we want to know what that ocean substructure looks likes,” Oliver said.

The goal is to decipher what exactly the penguins are responding to in the water that leads them to forage in some areas but not others. Early results suggest that tides may be a key factor. Oliver hypothesizes that as the tidal phase shifts from one big tide per day to two, the flow of water changes in such a way that it impacts the krill distribution and penguin behavior.

Other hypotheses involve ocean temperature and visual cues. The team will be examining at which depths the temperature is changing a lot, and whether there are certain optical parameters that are important because penguins are visual predators.

Penguins are a good indicator species for environmental change, Oliver said, because they integrate both large- and small-scale physics that affect ecosystem health. Overall the area is becoming less hospitable to Adélie penguins, which are either dying or need to move further south where there is more ice. Meanwhile other species of penguins, the land-loving Gentoos and Chinstraps, are moving in.

“If you look where the animals are going, they are going there for a reason,” said Travis Miles of Rutgers University via videoconference from Antarctica.

Rutgers is partnering with UD on the project by handling glider logistics in the field, and Kim Bernard from the Virginia Institute of Marine Science is contributing by sampling krill populations by boat. The study is funded by NASA in partnership with the National Science Foundation’s Long Term Ecological Research (LTER) Network site in Antarctica.

The experiments combine computer science, engineering, oceanography and biology, with researchers and graduate students constantly troubleshooting how to write code and analyze data in meaningful ways.

“We’ve got animals, robots, people, satellites,” Oliver said. “It’s been a really neat confluence of technology.”

Article by Teresa Messmore

Photo by Donna Patterson