ADVERTISEMENT

- Rozovsky wins prestigious NSF Early Career Award

- UD students meet alumni, experience 'closing bell' at NYSE

- Newark Police seek assistance in identifying suspects in robbery

- Rivlin says bipartisan budget action, stronger budget rules key to reversing debt

- Stink bugs shouldn't pose problem until late summer

- Gao to honor Placido Domingo in Washington performance

- Adopt-A-Highway project keeps Lewes road clean

- WVUD's Radiothon fundraiser runs April 1-10

- W.D. Snodgrass Symposium to honor Pulitzer winner

- New guide helps cancer patients manage symptoms

- UD in the News, March 25, 2011

- For the Record, March 25, 2011

- Public opinion expert discusses world views of U.S. in Global Agenda series

- Congressional delegation, dean laud Center for Community Research and Service program

- Center for Political Communication sets symposium on politics, entertainment

- Students work to raise funds, awareness of domestic violence

- Equestrian team wins regional championship in Western riding

- Markell, Harker stress importance of agriculture to Delaware's economy

- Carol A. Ammon MBA Case Competition winners announced

- Prof presents blood-clotting studies at Gordon Research Conference

- Sexual Assault Awareness Month events, programs announced

- Stay connected with Sea Grant, CEOE e-newsletter

- A message to UD regarding the tragedy in Japan

- More News >>

- March 31-May 14: REP stages Neil Simon's 'The Good Doctor'

- April 2: Newark plans annual 'wine and dine'

- April 5: Expert perspective on U.S. health care

- April 5: Comedian Ace Guillen to visit Scrounge

- April 6, May 4: School of Nursing sponsors research lecture series

- April 6-May 4: Confucius Institute presents Chinese Film Series on Wednesdays

- April 6: IPCC's Pachauri to discuss sustainable development in DENIN Dialogue Series

- April 7: 'WVUDstock' radiothon concert announced

- April 8: English Language Institute presents 'Arts in Translation'

- April 9: Green and Healthy Living Expo planned at The Bob

- April 9: Center for Political Communication to host Onion editor

- April 10: Alumni Easter Egg-stravaganza planned

- April 11: CDS session to focus on visual assistive technologies

- April 12: T.J. Stiles to speak at UDLA annual dinner

- April 15, 16: Annual UD push lawnmower tune-up scheduled

- April 15, 16: Master Players series presents iMusic 4, China Magpie

- April 15, 16: Delaware Symphony, UD chorus to perform Mahler work

- April 18: Former NFL Coach Bill Cowher featured in UD Speaks

- April 21-24: Sesame Street Live brings Elmo and friends to The Bob

- April 30: Save the date for Ag Day 2011 at UD

- April 30: Symposium to consider 'Frontiers at the Chemistry-Biology Interface'

- April 30-May 1: Relay for Life set at Delaware Field House

- May 4: Delaware Membrane Protein Symposium announced

- May 5: Northwestern University's Leon Keer to deliver Kerr lecture

- May 7: Women's volleyball team to host second annual Spring Fling

- Through May 3: SPPA announces speakers for 10th annual lecture series

- Through May 4: Global Agenda sees U.S. through others' eyes; World Bank president to speak

- Through May 4: 'Research on Race, Ethnicity, Culture' topic of series

- Through May 9: Black American Studies announces lecture series

- Through May 11: 'Challenges in Jewish Culture' lecture series announced

- Through May 11: Area Studies research featured in speaker series

- Through June 5: 'Andy Warhol: Behind the Camera' on view in Old College Gallery

- Through July 15: 'Bodyscapes' on view at Mechanical Hall Gallery

- More What's Happening >>

- UD calendar >>

- Middle States evaluation team on campus April 5

- Phipps named HR Liaison of the Quarter

- Senior wins iPad for participating in assessment study

- April 19: Procurement Services schedules information sessions

- UD Bookstore announces spring break hours

- HealthyU Wellness Program encourages employees to 'Step into Spring'

- April 8-29: Faculty roundtable series considers student engagement

- GRE is changing; learn more at April 15 info session

- April 30: UD Evening with Blue Rocks set for employees

- Morris Library to be open 24/7 during final exams

- More Campus FYI >>

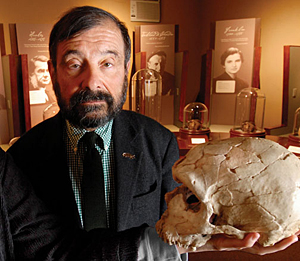

1:07 p.m., Nov. 20, 2009----Princeton University anthropologist Alan Mann spoke to a packed house when he delivered the third lecture in the University of Delaware's Year of Darwin Celebration on Thursday, Nov. 19. Mann's lecture addressed “The Question of Humanness: How Do We Define our Origins?”

His research considers a fundamental question that has occupied anthropologists, philosophers, psychologists, and now geneticists: How did we as primates become something special over time? What unique attributes do we have that enable us to look into the past and determine our own origins?

Mann admitted that despite decades of work, he still has more questions than answers.

“Is language the essential quality of humanness?” he asked. “And is language a prerequisite for the symbolic representation of art?”

Mann explained that language is an open-ended communication system that allows us to express completely new concepts as well as to understand new concepts expressed by others, even though we have never before heard those particular sequences of words.

“Language is a marvelous piece of equipment in our biological and cultural repertoire,” he said.

But again, Mann posed questions. “Did language appear suddenly, or did it evolve over time? Was it initially simpler and less flexible -- for example, unable to convey the concepts of past and future?”

Unfortunately, Mann said, fossil bones do not provide us with enough information to answer those questions definitively. We do know that other primates have the ability to connect symbols with objects -- for example, they can point to a picture of an apple if they would like to have one -- but there is no discrete order to their choices.

“They haven't mastered the idea of grammatical structure,” Mann explained, “which is the way we derive meaning from a series of words.”

With no current means to assess the origins of language, we have to look to other patterns to get at the core of humanness. One of those, according to Mann, is creativity.

“We can look at certain materials, which we find archaeologically, that may be able to tell us something about what it means to be human,” he said.

Tools are one example, and there is evidence that as early as 60,000 years ago, humans were using some very specialized and sophisticated tools. “The cognitive system that produced these items seems to have been very regularized,” Mann said.

The next round of evidence providing support for human creativity comprises ornaments such as pendants and shells. The latter were found hundreds of miles from their point of origin, suggesting their deliberate use for ornamentation or decoration.

Finally, about 35,000 years ago, representational art began to appear. According to Mann, the drawings and carvings found on cave walls provide evidence of modern humanity, which comprises a complex culture, language and symbolism, and a large complex brain with an interconnected and unique structure that enables speech production and comprehension.

Mann shared photographs of art from several caves in France and pointed out various patterns that remained static over tens of thousands of years, including a complete lack of background context for the animals represented in the sketches and carvings. “There is no landscape,” Mann said, “no mountains, no water, no grass, no trees -- just animals.”

The animals that appear in the pictures, especially the horses, typically have small heads, and the artwork features a number of repeated symbols, including gates, fences, and spears.

Techniques included the use of stencils, brushes, and even hands to indicate outlines and apply color. In many cases, the artists used perspective correctly and conveyed motion in their work. “These pictures show an enormous amount of interest and great genius,” Mann said.

In some cases, the work is characterized by patches of various colored pigments. “It looks as though they were experimenting with different colors in much the same way that we would test paint swatches on a wall to see which one we liked best before we painted the whole room,” Mann said.

Records of early art show few pictures of humans, and, when they do appear, the representations are remarkably primitive, given the level of sophistication and the amount of detail in the animal depictions.

Human hands, however, appear frequently in early art. “We don't know what this means, though,” said Mann. “Was it the artist's need to identify him or herself?”

Mann noted also that many of the hands show evidence of mutilation, including truncated digits. “Again, we don't know what this means,” he said. “Was the finger just folded down as part of some secret ritual? Was it actually gone, or was this just 'fun and games'? We have no way of telling.”

Mann closed with more questions. “Is this work really art?” he asked. “Did the 'artists' understand it as symbolic, or did it have some other purpose in their culture? We've identified it as art, and we admire the details, but we don't know its real purpose.”

UD's Year of Darwin Celebration launched last May in honor of the 200th anniversary of Charles Darwin's birth and the 150th anniversary of the publication of his landmark work, On the Origin of Species.

Karen Rosenberg, professor and chairperson of the Department of Anthropology, chairs the University committee that organized the series. The lectures are co-sponsored by International Education Week, the Center for International Studies and the Department of Anthropology, with additional support from the Provost's Office, the College of Agriculture and Natural Resources, the Science, Ethics and Public Policy Program, and the following departments: Biological Sciences, English, Geography, Geological Sciences, Linguistics and Cognitive Science, and Philosophy.

The series will conclude Dec. 7 with “What Darwin Got Wrong,” by Jerry Fodor from Rutgers University. That lecture will begin at 3:30 p.m. in 120 Smith Hall.

Article by Diane Kukich