By tracey bryantOffice of Communications & Marketing

When Richard Heck was in his early teens, his father moved the family from Massachusetts to a brand-new house on a barren lot in California. Heck, an only child, was given the task of landscaping.

"We had an empty yard, and it was my job to select and install the plants," he says. "I got concerned with fertilizers and sprays and realized I needed to know more about the nutrients and pigments in plants. That got me into chemistry, and I followed it into high school and the university, and I haven't regretted it."

On Dec. 10, 2010, in a stately ceremony in Stockholm, Heck, the Willis F. Harrington Professor Emeritus in the University of Delaware Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, was presented the Nobel Prize in Chemistry by King Carl XVI Gustaf of Sweden.

Heck, who was recognized first, and Ei-ichi Negishi of Purdue University and Akira Suzuki of Hokkaido University in Sapporo, Japan, were cited "for palladium-catalyzed cross couplings in organic synthesis." The scientists, who shared a $1.5 million award, were honored for discovering "more efficient ways of linking carbon atoms together to build the complex molecules that are improving our everyday lives."

The University of Delaware community was ecstatic as they watched the live webcast of the awards ceremony. Fellow chemists at UD and beyond praised Heck's accomplishments.

"It is wonderful to see our colleague honored so prominently," said Klaus Theopold, chairman of the University's Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry. "Dick Heck did his ground-breaking work at UD in the very early days of organometallic chemistry, and even back then he thought deeply about reaction mechanisms. I remember being inspired by a book of his as a graduate student. Its title, Organotransition Metal Chemistry — A Mechanistic Approach, set the agenda for scores of researchers who followed in his footsteps. Heck's contributions extend well beyond the reaction he is now rightly famous for, and we are pleased to no end that he is finally getting the recognition he deserves."

Prof. E. J. Corey of Harvard University, who won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1990, said that recognition for the palladium catalysis discoveries was overdue and may have been delayed by the field's multifaceted nature and its sizable number of distinguished scientists.

"In my mind, Dr. Richard F. Heck stands out among this group as the obvious and early pioneer whose work was not only exceedingly original and important, but also of great heuristic value. He awakened the community of synthetic chemists to the revolutionary nature of palladium catalysis.

"Dick Heck is a modest and admirable person. I hope that the award of the Nobel Prize brings him the satisfaction of knowing how greatly his peers value his contributions to the science of chemistry," Corey said.

"The impact of Heck's chemistry in the field of pharmaceutical manufacturing has been profound," noted William A. Nugent, senior scientific fellow at Vertex Pharmaceuticals. "At my company, palladium coupling is used in the synthesis of over half the drugs currently under development, and I believe this experience is typical across the pharmaceutical industry. Indeed, it is difficult to imagine how some of these molecules could be synthesized at all without chemistry which is traceable to Heck's seminal contributions."

When Heck graduated from high school, his parents encouraged him to continue his education. His father was a salesman in a department store, and his mother a housewife. Neither had a college degree.

Heck enrolled at UCLA and earned a bachelor's degree in chemistry in 1952 and a doctorate in 1954, working under the supervision of Prof. Saul Winstein, whom Heck deemed "brilliant."

"He had a very good reputation, and that's why I went to work for him," Heck says.

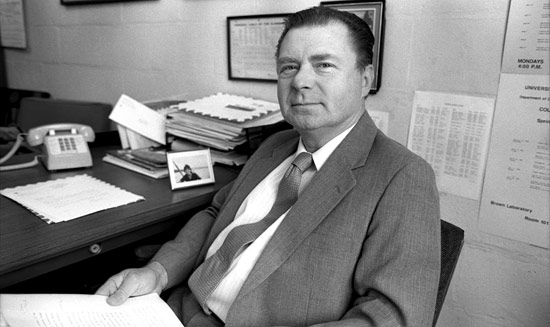

After postdoctoral research in Winstein's lab, Heck took a position with Hercules in Wilmington, Del., in 1957. In 1971, he joined the faculty in the UD Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, where he remained until his retirement in 1989.

While at UD, he discovered the "Heck Reaction," which uses the metal palladium as a catalyst to get carbon atoms to connect up —a difficult feat in nature.

The discovery has enabled the production of new classes of pharmaceuticals for treating cancer to HIV, asthma, migraine headaches, stomach ailments and other maladies. The work revolutionized DNA sequencing, making possible the coupling of organic dyes to the DNA bases, which was essential for the Human Genome Project. Heck's achievements reverberate throughout our lives every day, in products ranging from sunscreens to super-thin computer monitors.

Rather than a "Eureka moment," Heck says the research "sort of grew slowly and developed into something of value. When you're doing the work, you don't know what's going to become of your efforts. It was not clear in the beginning that this was going to be anything special."

Susan James was hired in 1974 to be Heck's secretary. An administrative assistant in the department today, she remembers her former boss and now-Nobel laureate as a prolific writer.

"He was very serious and dedicated. It seemed that he was publishing at least one journal article a month," she says, recalling the multi-step roll-the-paper-in, roll-the-paper-out process on her IBM Selectric typewriter to make the long dashes forming the sides of the hexagonal benzene molecules in scientific figures.

Today, Heck says, his research days are over and he is "completely retired. I've done my share," he notes simply.

Coming full circle, he's back working with plants, raising orchids at home in Quezon City, the Philippines, with his wife, Socorro. They've been married since 1979.

"I really enjoyed my chemistry very much, and that's why I think I was successful," he says. "It was a fascinating subject to me and things worked out well for me, which led me to keep at it."

By author creditOffice of Communications & Marketing

On Thursday, May 26, 2011, the University of Delaware will host "Frontiers in Catalysis," a symposium in honor of Richard F. Heck, Willis F. Harrington Professor Emeritus of Chemistry and Biochemistry, and winner of the 2010 Nobel Prize in Chemistry. Register at www.udel.edu/nobelsymposium/.

"Prof. Heck's discoveries have changed the world, leading to significant advancements in human health and medicine to electronics and energy research," said UD President Patrick Harker. "We are delighted to welcome him back to the University of Delaware for this day of science and celebration, honoring his ground-breaking contributions."

The chemical process Heck invented, known as the "Heck Reaction," fundamentally changed how molecules are made, according to Tom Apple, University provost and professor of chemistry. Apple was a graduate student in the Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry when Heck was on the faculty.

"Dick Heck's research launched entire new classes of pharmaceuticals for fighting diseases such as cancer," Apple said. "His work was essential for the Human Genome Project and fields such as proteomics, as well as the development of new energy technologies ranging from organic LEDs to sugar-based fuel cells."

The symposium will feature internationally prominent speakers from academia and industry. Heck's co-laureate Ei-ichi Negishi, the Herbert C. Brown Distinguished Professor of Chemistry at Purdue University, will deliver the keynote address as the 2011 Heck Lecturer.

Other speakers include Stephen L. Buchwald, the Camille Dreyfus Professor of Chemistry at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology; Todd Nelson, director of pharmaceutical sciences at Merck; Melanie Sanford, professor of chemistry at the University of Michigan; Victor Snieckus, Bader Chair in Organic Chemistry at Queen's University; and Dean Toste, professor of chemistry at the University of California Berkeley.

Primary sponsors include the University of Delaware through the Office of the Provost, the College of Arts and Sciences, and the Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry; Dow Chemical Company; and Ashland Inc.

Additional support is being provided by the American Chemical Society, DuPont, the Center for Catalytic Science and Technology at UD, and the Delaware Biotechnology Institute.

By author creditOffice of Communications & Marketing

New Pharmaceuticals

The Heck Reaction revolutionized the manufacture and discovery of drugs — for treating arthritis, cancer, HIV and many other diseases. The painkiller Aleve and asthma treatment Singulair are just a few examples.

DNA Sequencing

A modification of the Heck Reaction, Sonogashira Coupling, is key to preparing the fluorescent dyes in DNA sequencing — essential for the Human Genome Project, disease research and forensics.

Sun Protection

Sunscreens and sun-protective cosmetics rely on the Heck Reaction for the production of octyl methoxycinnamate, a compound that absorbs the sun's UV rays and is used to reduce the appearance of scars.

Future Electronics

PPV, a polymer made with the Heck Reaction, emits light in response to an electrical current, thanks to a layer of organic compounds. Organic LEDs are being used in the screens of next-generation TVs, smart phones and computers.