Bash: Input/Output

Demonstration project

Project description

-

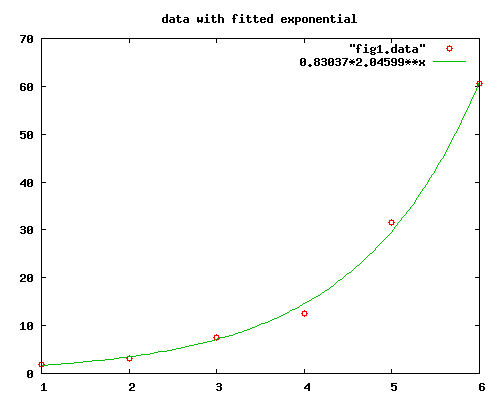

You have a data file with two variables per line, with a space separating the x and y values. You also have a function of x as a string. Your project is to create an xy plot of the data along with the function. You are to use gnuplot, which is a program which deals with files by filenames. Your script with do two things.

- Echo on STDOUT a simple gnuplot command file (you will be given a template)

- Read on STDIN the data file and transform it to a simple x, y line with a comma and space separating the x and y, While reading you are to check for simple warnings and errors and output any error messages on STDERR.

You will be given a gnuplot template file, and you can assume that your data file has well formed, space separated numbers. There may be two few numbers or two many numbers.

echo to write out STDOUT (or STDERR),

and read read from STDIN. The use of these two will

be developed step-by-step. The shell logical will done by using the

if statement and while statement. Finally this

will all be put to together in one shell statements with the code blocks

put into functions.

Topics:

The following sections have several files listed, which are all

shell scripts. They begin with sha-bang comment, which means they will run

as a bash shell script when the file is executable and you begin the command

with the file name. Following the file listing, there is a test session

with testing$ as the prompt

note: On the centos.css.udel.edu they are in

the directory /usr/share/WS5. You can copy them to your working

directory, make sure they are executable and try them using the ./filename

to make sure you are running the script in your current working directory

Output with echo

The echo shell command will print the values of the arguments to

standard out (STDOUT), which normally appears

in the terminal session after the command is completed, however STDOUT can be redirected

with a command redirection in the

form >filename.

It is best if you quote the arguments of the echo command, which makes

combines them into one argument, using single quotes for a literal string, and double quotes for

a strings when you

want variables expanded to their values using the $ notation.

The first example prints a three line file using one literal string with the

line endings (CR) in the string creating new lines. The file contains three

gnuplot commands: a set terminal, a set output, and

a plot command.

#!/bin/bash echo 'set terminal svg size 400 300 set output "fig1.svg" plot "fig1.data" with points pointtype 6, 2**x'

The output file will tell

the gnuplot program to produce figure 1 as a

scalable vector graphic

(svg) in

the file fig1.svg from the

data in fig1.data.

note: Inside a single quoted string no characters have special meaning and

will all appear in the string. This includes the new line character, return, which

will allows a multi-line output with one echo command.

testing$ ./echo1

set terminal svg size 400 300

set output "fig1.svg"

plot "fig1.data" with points pointtype 6, 2**x

testing$ ./echo1 >commands

testing$ wc -l commands

3 commands

The first echo1 test command prints to the terminal.

The second echo1 command redirects

the output to the file commands. The wc -l command counts the

lines in the file and prints the expected answer of 3 lines. The echo

command puts a return at

the end of the string so the number of lines in the file is the number of

returns in your

string plus 1.

#!/bin/bash imagefile='fig2.svg' datafile='fig2.data' function='0.83037*2.04599**x' echo -n "\ set terminal svg size 400 300 set output \"$imagefile\" plot \"$datafile\" with points pointtype 6, $function "

The echo2 version uses double quotes. The variables are expanded

to the values set in the environment, and the backslash is the escape character. Here

the string starts with an escaped return. This way all the lines following with

be aligned just the way the appear in the output stream. Variables are expanded

to the values by the use of the $.

The \" is need for double

quotes in the output. The string ends with an double quote and the beginning of

a line. The -n option on the echo command prevents an

extra line from being appended to the output.

note: Inside a double quoted string their are 4 characters with special meaning and

for them to appear in the string. The quotes \", \$, \` and \\

all expand as one character, a

single \ at the end of a line, escaped return, is expanded as null, which means

the lines are joined together.

note: It is good practice to choose meaningful variable names to save

parts fo the file to be created.

It makes more sense to a reader of your code who does not

know gnuplot, and you may later uses the variables to create other files. For example,

you may want to use the width, height and imagefile

variables to write an html file for display of

the plot.

testing$ ./echo2 >commands

testing$ cat commands

set terminal svg size 400 300

set output "fig2.svg"

plot "fig2.data" with points pointtype 6, 0.83037*2.04599**x

testing$ wc -l commands

3 commands

The echo2 command saves

the output to the file commands. The cat command

outputs to the terminals just as the echo command would have done, but the

file is save for used by the command wc -l to count lines.

#!/bin/bash source .echorc if [ "$title" ]; then echo -n "\ set title \"$title\" " fi echo -n "\ set terminal svg size $width $height set output \"$imagefile\" plot \"$datafile\" with points pointtype 6, $function "

The echo3 version reads the variable assignments from

a hidden run control file .echorc.

note: This is a neat trick to leverage

the shell parser to parse your setup file. This way you can run the same shell,

unchanged, to make several figures. The size of the figures, the file names

and the function are all taken from the .echorc.

The variable imagefile should have a file name as its value.

Here a case statement to select the echo to write the appropriate two commands, based

on the suffix of the image file name. The two cases are svg are png. There is

different format of the set terminal gnuplot command.

testing$ cp fig1rc .echorc testing$ ./echo3 set title "data with fitted exponential" set terminal svg size 500 400 set output "fig1.svg" plot "fig1.data" with points pointtype 6, 0.83037*2.04599**x testing$ cp fig2rc .echorc testing$ ./echo3 set title "figure2: data with function 2**x" set terminal svg size 500 400 set output "fig2.png" plot "fig2.data" with points pointtype 6, 2**x

For this test there is a sample run control files fig1rc

and fig2rc. Before each test the files are copied to

.echorc. Both tests are getting the title, file names

and the function from the rc files.

What happens if the variables function and title

are missing from the .echorc file. To test we can use the

head -4 command to copy just the first for lines of the

configuration file to .echorc.

testing$ head -4 fig2rc > .echorc testing$ ./echo3 set terminal svg size 500 400 set output "fig2.png" plot "fig2.data" with points pointtype 6,

There are two problems with this version.

- The image file is an

svg, but it is written to apngfile. We want to set the terminal type on the gnuplot command base on the suffix of the image file name. - There is a dangling comma at the end of the plot command.

#!/bin/bash

source .echorc

case "$imagefile" in

*.png )

echo -n "\

set terminal png transparent size $width,$height

set output \"$imagefile\"

"

;;

*.svg)

echo -n "\

set terminal svg size $width $height dynamic

set output \"$imagefile\"

"

esac

echo -n "\

plot \"$datafile\" with points pointtype 6${function:+, }$function

"

The echo4 version reads the variable assignments from

a hidden run control file .echorc. The

shell case statement to select on of two

forms of the gnuplot commands. Wild card matchins is use

to select svg (*.svg) or png (*.png).

testing$ cp fig1rc .echorc testing$ ./echo4 set terminal svg size 500 400 dynamic set output "fig1.svg" plot "fig1.data" with points pointtype 6, 0.83037*2.04599**x testing$ cp fig2rc .echorc testing$ ./echo4 set terminal png transparent size 500,400 set output "fig2.png" plot "fig2.data" with points pointtype 6, 2**x testing$ head -4 fig2rc >.echorc testing$ ./echo4 set terminal png transparent size 500,400 set output "fig2.png" plot "fig2.data" with points pointtype 6

For this test there is a sample run control files fig1rc

and fig1rc. Before the

first test we pipe the output of cat fig1rc command to the

tee .echorc command. This results in copying the fig1rc

file to .echorc

file with the output also being displayed to the STDOUT. To test the

png case the sed command will change svg to png before piping

it to the same tee command.

Input with read

The read shell command will parse text upto a line ending from STDIN

and assign the tokens to the variable names in the argument list. The tokens

on the line are parsed just as the shell commands, with white space between

tokens and a backslash to continue the line to the next physical line. If there

are more tokens then variables then the remainder of the line will be assigned

to the last variable. In particular if there is only one variable then all the

line, excluding any leading white space, will be assigned the variable.

#!/bin/bash read line echo $line

This is a simple combination of a read write, but it is a little too

simple. When reading data you should always use the raw option -r

to avoid problems with backslash quoting.

testing$ ./read1 1 1.8 1 1.8 testing$ ./read1 >save 1 1.8 testing$ cat save 1 1.8 testing$ ./read1 >save 1 1.8\ 2 3.4 testing$ cat save 1 1.82 3.4

The first read1 command reads from the terminal and echos

back what was type. The second reads one line from the terminal and saves

it in a file.

The third shows how the backslash continues the line. The

quoted return logically joins two physical lines.

note on backslashes: We do not expect any backslashes in the data file, but it is

a good practice to always use read -r to avoid backslash quoting and

line continuation. Perhaps someone will try to break your program with a backslash

in the data file.

#!/bin/bash read -r x y etc echo "$x, $y"

For this project we want to change the data to put a comma between the

first two tokens in the data file. This version read will read the first two

columns from the line and echo the pair with a comma separator. The value of

the etc variable will contain any additional text on the line.

testing$ ./read2 x y unwanted data\ x, y testing$ head -1 goodfile 1 1.8 testing$ ./read2 <goodfile 1, 1.8

The first read2 reads from and echos to the terminal without backslash

quoting. Here we test this with extra text and a final backslash. The raw option

does what we expect this this input.

The command head -1 prints the first line of the file.

The second read2 command redirects to command to

take one line of input from the file goodfile.

#!/bin/bash read -r x y etc if [ -n "$etc" ]; then echo "line too long, unexpected: $etc" >&2 elif [ -z "$y" ]; then echo "line too short" >&2 fi echo "$x, $y"

We have seen that the etc variable will contain any extra, unwanted data.

It should be empty. Also if there is only one number then the y string will be empty.

This gives two simple tests to check for bad lines in the data file.

The read3 will echo all the lines to STDOUT, and echo all error

messages using the >&2 redirect (STDERR).

note on if: The if command is terminated by fi. Type

help if for the details. The [ following the if is

a shell command and must be a token surrounded by white space. Also, if you put the

then command on the same line as the test you must terminate the test command with a

semicolon.

testing$ ./read3 1 1.8 1, 1.8 testing$ ./read3 1 1.8 2 3.4 line too long, unexpected: 2 3.4 1, 1.8 testing$ ./read3 1 line too short 1, testing$ ./read3 >save 1 1.8 junk line too long, unexpected: junk testing$ cat save 1, 1.8The first three

read3 commands test the command with three commands: a correct line

with

extra spaces, a line with extra data, and a line without a y value. The last read3

command shows the usefulness of redirect to STDERR. We we save the file with the

redirect command, the error messages are still sent to the terminal, and the

save file is not cluttered with error messages. We may want to take the

"too long" message as a warning and still proceed with saved file.

Now we are reading to develop a way to read all the lines in a file

Input with while loop

The read shell command will read one line from STDIN, and if it encounters

an end for file, i.e., there is not more data to read, it will return a non-zero status.

This is designed to work in the while loop.

#!/bin/bash

while read -r x y etc; do

if [ -z "$y" ]; then

echo "line too short" >&2

elif [ -n "$etc" ]; then

echo "line too long, unexpected $etc" >&2

fi

echo "$x, $y"

done

All the commands in the

do block are executed once for every line with x, y and

etc

assigned to the first, second and remainder tokens in the file.

testing$ ./while1 <badfile >fig1.data line too short line too long, unexpected: 32 testing$ cat badfile 1 1.8 2 3.2 3 4 12.6 5 31.5 32 6 60.5 testing$ cat fig1.data 1, 1.8 2, 3.2 3, 4, 12.6 5, 31.5 6, 60.5

The while1 command reads all the lines of the redirected file and writes

to fig1.data. The sample files, badfile, has two errors,

one too short and one two long. It is clear the too short condition is worse

then the too long condition. We will consider one warning and one an error.

It would be useful if the error message contain the line number to locate the error.

#!/bin/bash

let lineNo=0

while read -r x y etc; do

let lineNo+=1

if [ "$x" -a -z "$y" ]; then

echo "line $lineNo too short" >&2

errCode=1

elif [ "$etc" ]; then

echo "line $lineNo too long, unexpected $etc" >&2

fi

echo $x${y:+, }$y

done

[ -z "$errCode" ]

:

To make the error and warning messages more informative we have added two variable.

The integer variable lineNo to count lines in the file, and the

string variable errCode to flag an error condition. The let

command is for integer variables and allows

arithmetic on integer variables. Here we start by assigning

lineNo to 0 and then increasing it by 1 as

the very first command in the do block. Any variable which is unassigned

will expand as a null string. So we expect $errCode to be null after the

while loop is completed when no errors were encountered. Since the implied exit

and the end of the script will exit with status of the last command, this script with

have a success exit if the errCoded is never assigned. A blank

line is not an error.

testing$ ./while2 <badfile >fig1.data && echo "good data file" line 3 too short line 5 too long, unexpected 32 testing$ ./while2 <warningfile >fig1.data && echo "good data file" line 3 too long, unexpected 8 line 5 too long, unexpected 32 good data file testing$ ./while2 <goodfile >fig1.data && echo "good data file" good data fileTo test

while2 we have added a warningfile

which as an added value on two lines. We test twice, the badfile sends finds two

bad lines and returns a failed status, and that is why the good data file

is not echoed. The test with the warning file also finds two bad lines,

but long lines are only warnings. After the too warning,

the good data file appears, as it does for the goodfile.

Putting it together with functions

makefig script

A bash function is a block of commands which is invoked

in your shell by just using the name. The commands are execute much

as with the arguments $1 ... $n set to the arguments on the

invoking statwment. The file makefig has the completed script will

the scripts we

developed above as functions:

- gnucommands

- function to write our gnuplot command file on STDOUT

- datafile

- function to read our data file on STDIN and out the transformed data file on STDOUT. Error messages are written on STDERR and the shell variable $errcode is set to 1 if an error was encountered.

- die

- Utility function to write an error message and exit with an

failedreturn code.

function name { COMMANDS }

#!/bin/bash

# makefig

# takes std input data file and makes a gnuplot figure

# Define functions:

# die, gnucommands, datafile

function die {

echo "makefig: $@" >&2

exit 1

}

function gnucommands {

if [ "$title" ]; then

echo -n "\

set title \"$title\"

"

fi

case "$imagefile" in

*.png )

echo -n "\

set terminal png transparent size $width,$height

set output \"$imagefile\"

"

;;

*.svg )

echo -n "\

set terminal svg size $width $height dynamic

set output \"$imagefile\"

"

esac

echo -n "\

plot \"$datafile\" with points pointtype 6${function:+, $function}

"

}

function datafile {

let returncode=0

let lineNo=0

while read -r x y etc; do

let lineNo+=1;

if [ "$x" -a -z "$y" ]; then

echo "line $lineNo too short" >&2;

returncode=1;

elif [ -n "$etc" ]; then

echo "line $lineNo too long, unexpected: $etc" >&2;

fi

echo $x${y:+, $y}

done

}

function die {

echo "Error: $@" >&2

exit 1

}

#-----

# Get variables from run control file:

# function, datafile, commandfile, imagefile, height, width

source .makefigrc

[ "$datafile" ] || die "no data file"

[ "$commandfile" ] || die "no command file"

#-----

# Make output files:

# datafile, commandfile, imagefile

datafile >$datafile

[ $returncode -eq 0 ] || die "some lines to short"

gnucommands >$commandfile

gnuplot $commandfile

- Define functions

-

The three functions are defined. The first two are the same as

echo3andwhile2with a few additions:- There is an if block in the

gnucommandto insert a gnuplot command to add a title to the plot, if it is present. - The bash variable

functionis added to the line with${function:+, $function}. This only adds to comma if the $function is present. This prevents a bare comma form being added to the plot command, and thus thefunctionvariable is now optional.

command. The last statement is the gnuplot command with the command file name as it's only argument. gnuplot must be in your path, and it's return code will determine the return code of the entire script.

The

diefunction is a utility function to make it easier to write and error message and exit with a failed exit status. (This will be familier if you have ever looked at Perl code.) It is used in the form[ test which should be true to continue ] || die "message when condition not met"

For example, the variabledatafilemust be set, or else the redirect will fail, and we do not want to continue.[ "$datafile" ] || die "no data file";

- There is an if block in the

- Get variables from run control file

-

The

.makefigrcfile is sourced to assign some important variables. The variablesdatafileandcommandfileare checked to make sure the are assigned. - Make output files

- The functions are used to make the files. The last statement is the gnuplot command with the command file name as it's only argument. gnuplot must be in your path, and it's return code will determine the return code of the entire script.

Testing makefig1

Firefox will be used to see the plot generated by gnuplot. These are either Scalable Vector Graphics (svg) or Portable Network Graphics (png). Firefox should be able to view either by themselves or embedded in an html file. We must start firefox from the command line, in the background.testing$ firefox & [1] 4794 testing$

The ampersand causes firefox to run in the background.

You get a prompt to continue your shell session, while firefox

is running. If you forget the ampersand you can continue in your

shell typing ctl-z, this will cause firefox

to be suspended. Type bg to put firefox in the background,

you will see the command repeated with the ampersand.

The number, 4794 is the process id, you can use this to

kill firefox later. (It is better to just quit firefox in the normal

way, with the File pulldown menu.) You can always

find the process id with the command

pgrep firefox

This will give you all firefoxes running. Remember this is a multi-users system. To just see yours:

pgrep -u $USER firefox

Once firefox is running in the background you a command line command such as:

firefox fig1.png

To have firefox render the png in a new tab in the firefox window. To close the tab click on thex in the tab. You should get a prompt

to continue you shell.

Now test makefig1.

<testing$ alias makefig=./makefig1 testing$ cp fig1rc .makefigrc testing$ makefig <badfile && echo "figure ready" line 3 too short line 5 too long, unexpected: 32 makefig: some lines to short testing$ sed -n '3p;5p' badfile 3 5 31.5 32 testing$ makefig <warningfile && echo "figure ready" line 3 too long, unexpected: 8 line 5 too long, unexpected: 32 figure ready testing$ sed -n '3p;5p' warningfile 3 7.5 8 5 31.5 32 testing$ makefig <goodfile && echo "figure ready" figure ready testing$ sed -n '/imagefile=/p' .makefigrc imagefile='fig1.svg' testing$ firefox fig1.svg testing$Error message from Firefox:

This XML file does not appear to have any style information associated with it.We will modify the

makefigrc file to use png instead

of svg.

testing$ sed 's/.svg/.png/g' fig1rc >.makefigrc testing$ makefig <goodfile && echo "figure ready" figure ready testing$ grep imagefile .makefigrc imagefile='fig1.png' testing$ firefox fig1.png testing$

makefig script version

Thismakefig1 will make a figure, but there a few usabily issues

we will address with a second version.

- When the script is successful in exits normally with no output. (This is

typical of most UNIX commands.) We will add a option

-vto produce as short report of what the gnuplot command will produce. - Typically, you will have one "run control" file for each figure you

want to make. Instead of coping in individual file to the hidden

run control file, a new

option

-f filenamewill read the variable assignments forfilenameinstead of.makefigrc. - To quickly add a function to the plot, we will take all the arguments and make a comma separated list of functions, which will be added to the figure.

#!/bin/bash

# makefig:

# takes std input data file and makes a gnuplot figure

# options:

# -v for more reporting

# -f filename to set run control file

# arguments:

! functions of x to be added to the figure

#-----

# Define functions:

# die, gnucommands, datafile

function die {

echo "makefig: $@" >&2

exit 1

}

function gnucommands {

if [ "$title" ]; then

echo -n "\

set title \"$title\"

"

fi

case "$imagefile" in

*.png )

echo -n "\

set terminal png transparent size $width,$height

set output \"$imagefile\"

"

;;

*.svg )

echo -n "\

set terminal svg size $width $height dynamic

set output \"$imagefile\"

"

esac

echo -n "\

plot \"$datafile\" with points pointtype 6${function:+, }$function

"

}

function datafile {

let returncode=0

let lineNo=0

while read -r x y etc; do

let lineNo+=1;

if [ "$x" -a -z "$y" ]; then

echo "line $lineNo too short" >&2

returncode=1;

elif [ "$etc" ]; then

echo "line $lineNo too long, unexpected $etc" >&2

fi

echo $x${y:+, }$y

done

}

#-----

# Get variables for argument list

# verbose 0|1

# rcfile run control file with assignments

# argfuns list of functions to plot

rcfile='.makefigrc'

verbose=0

while [ $# -gt 0 ]; do

case $1 in

-v)

verbose=1

;;

-f)

shift

rcfile="$1"

;;

-[!0-9]*)

die "illegal option $1

Usage: `basename $0` [-v] [-f file] [function ...]"

;;

*)

argfuns="$argfuns${argfuns:+, }$1"

esac

shift

done

#-----

# Get variables for run control file

# title, width, height, imagefile, datafile

source $rcfile

[ "$datafile" ] || die "no data file"

[ "$height" -a "$width" ] || die "no plot dimensions"

function="$function${function:+${argfuns:+, }}$argfuns"

case "$function" in

*,*)

functions="functions $function"

;;

?*)

functions="function $function"

esac

#-----

# Make file

# datafile

datafile >$datafile

[ $returncode -eq 0 ] || die "some lines too short"

#-----

# Print formated report

[ $verbose -eq 0 ] || echo "

${title:-figure:}

Make a plot of data points in the file

$datafile${functions:+ together with the $functions}.

The plot will be sized at $width by $height, and stored

in the file $imagefile.

" | fmt

#-----

# Make figure

gnucommands | gnuplot

Testing makefig2

testing$ alias makefig=./makefig2

testing$ sed 's/.svg/.png/' fig1rc >.makefigrc

testing$ makefig -h <goodfile && firefox fig1.png

makefig: illegal option -h

Usage: makefig2 [-v] [-f file] [function ...]

testing$ makefig -v <goodfile && firefox fig1.png

data with fitted exponential

Make a plot of data points in the file fig1.data together with

0.83037*2.04599**x. The plot will be sized at 500 by 400, and stored

in the file fig1.png.

--- New tab in firefox with fig1.png

testing$ makefig -v -f fig2rc "0.83037*2.04599**x" <badfile && firefox fig2.png

line 3 too short

line 5 too long, unexpected 32

makefig: some lines too short

testing$ makefig -v -f fig2rc "0.83037*2.04599**x" <goodfile && firefox fig2.png

figure2: data with function 2**x

Make a plot of data points in the file fig2.data together with 2**x,

0.83037*2.04599**x. The plot will be sized at 500 by 400, and stored

in the file fig2.png.

--- New tab in firefox with fig2.png

testing$ makefig -v -f fig3rc <goodfile && firefox fig3.png

figure3: nearly exponential data

Make a plot of data points in the file fig3.data. The plot will be

sized at 500 by 400, and stored in the file fig3.png.

--- New tab in firefox with fig3.png

testing$ makefig -v -f fig3rc "2**x" "exp(x)"<goodfile && firefox fig3.png

figure3: nearly exponential data

Make a plot of data points in the file fig3.data together with ,

2**x, exp(x). The plot will be sized at 500 by 400, and stored in

the file fig3.png.

gnuplot> plot "fig3.data" with points pointtype 6, , 2**x, exp(x)

^

line 0: invalid expression

testing$ makefig -v -f fig3rc "-0.358 - 0.0756*x**2 + 0.0000559*x**4 + 2**x" <goodfile

makefig: illegal option -0.358 - 0.0756*x**2 + 0.0000559*x**4 + 2**x

Usage: makefig2 [-v] [-f file] [function ...]

testing$

University of Delaware

Last updated: August 11, 2010

Copyright © 2010 University of Delaware