UDAILY is produced by the Office of Public Relations

150 South College Ave.

Newark, DE 19716-2701

(302) 831-2791

|

|

NIMH awards UD psychologist four-year grant for 'boundary extension' research

3:45 p.m., Aug. 6, 2003--Seeing is believing. Or maybe not, according to University of Delaware researcher Helene Intraub, a professor of psychology who has conducted extensive experiments in perception, memory and visual illusions.

|

| Intraub finds that boundary extension applies to the sense of touch, as well as sight. Blindfolded subjects who feel objects, their layout and their relation to boundaries also remember having touched the area just beyond the borders. |

In the course of her research on perception and memory, Intraub has discovered that people tend to share a common error when remembering a photograph of a scene. They remember parts of the scene that were not in the photograph but were likely to have existed just beyond the boundaries of the view—a phenomenon she refers to as “boundary extension.”

The National Institute of Mental Health recently awarded Intraub a four-year $739,000 grant to continue her work in understanding these constructive errors and the beneficial role they may play in everyday perception.

“When we think of memory errors, we often think of them as failures,” Intraub said. Memory errors that are detrimental have been studied for many years, particularly in the context of eyewitness testimony, she said, adding there are cases in which witnesses incorrectly remember the details of a crime not because they are lying but because of errors in memory.

“There is a lot of research on what is called the ‘misinformation effect,’” she said. “People can honestly confuse newly provided information with what they originally saw. For instance, over the course of several different police interviews, depending on the quality of the original memory and the interview techniques used by the interviewer, researchers raise the concern that new information can taint memory for an incident.”

In contrast, what is so intriguing to Intraub about boundary extension is that “although it is certainly error, it is an error than is apparently shared by everyone, and an error that usually provides an excellent prediction of what really did exist beyond the boundaries of the view,” she said.

Boundary extension occurs under conditions in which one would expect memory to be quite accurate, she said. For example, when viewers were shown a series of close-ups and then were shown the exact same picture minutes later, they tended to reject them as being the same, remembering instead that the original pictures had shown a more wide-angle view. This error can occur as soon as one second after viewing the picture.

Artists who have participated in these experiments make the same error, Intraub said, and recent research from other laboratories has shown that both young children and elderly viewers are prone to make the same error when remembering scenes.

|

|

|

|

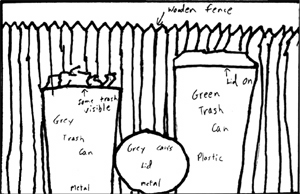

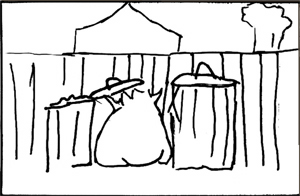

| Experimental subjects tend to remember having seen a greater expanse of a scene than was shown in a photograph. For example, when drawing from memory the close-up view of the trash cans (top left), the subject’s drawing (bottom left) included extended boundaries. Another subject, shown a more wide-angle view of the trash cans (top right), also drew the scene with extended boundaries (bottom right). |

Strangely enough, warning people about the phenomenon does not prevent its occurrence. In fact, Intraub and her students continue to be prone to the error themselves. “Why would memory fail so consistently, in the same way for so many people? Why should such an error occur at all?” she asked.

Intraub suggested that one can begin to answer these questions by considering a classic puzzle in the field of visual perception.

“Although we all have the impression that we see everything at once, we actually don’t,” she said. “The human observer can only see a very small part of the world in sharp detail at any one time.”

Intraub said the human field of view encompasses about 200 degrees of visual angle in width and 150 degrees in height, but out of that entire field only about 1-2 degrees of visual angle—an area about the size of a thumbnail held at arm's length—can be seen with high acuity.

“Although the world around us in continuous, perceptual input is made up of a succession of discrete inputs,” she said. “Our eyes scan a scene by making eye movements that rapidly shift the position of the high acuity region of vision from one location to the next. Eye position can shift as quickly as three to four times per second. Although we don’t realize it, while the eyes are in motion vision is suppressed. The brain must rely on memory for what was present in the last glimpse.”

Intraub said cognitive scientists have puzzled over the question of how it is that people perceive a smooth and continuous world when visual input consists of a discrete succession of snapshots in which only the central region can be clearly seen.

To provide a coherent mental representation of our continuous surroundings, Intraub said the brain has adapted by ignoring the spurious boundaries of a given view and extrapolating beyond its edges.

“Boundary extension may be a distortion of memory that is adaptive in that it helps people to integrate successive views of the world,” she said. “Anticipated continuity of the scene becomes embedded in their memory that causes them to remember seeing what was likely outside the boundaries. The brain is capable of extrapolating the continuation of the perceived surfaces and objects in a given view. To the mind, looking at a photograph of a scene is like looking at the world through a window. The world continues beyond the window frame.”

Although photographs and pictures are the most usual type of stimulus that vision scientists use to explore scene perception, Intraub wanted to be sure that boundary extension was not limited to perception of two-dimensional images. To determine if the phenomenon would generalize to memory for real three-dimension scenes, she and her students developed a new methodology in which real objects and surfaces were set up in the lab the way they are in common scenes viewers see all the time. Common household objects were used to create scenes of a kitchen and a workbench, among others

In these experiments, participants view a small part of the constructed scene through a simple window frame. The frame is taken away and minutes later they return and are asked to reconstruct the original location of the borders.

“Even though the scenes were directly in front of them, and they could see the size of the objects and the window frame with respect to their body, again, participants consistently remembered the boundaries as being farther apart, showing more of the background than they had actually seen before,” Intraub said.

Blindfolded participants who feel the objects, their layout and their relation to the boundaries also remember having touched the area just beyond the borders, she said. The same was true of a young woman who is an expert at using touch and movement to explore the world because she has been deaf and blind since early life.

|

Helene Intraub

Photo by Kathy Atkinson

|

Because of these findings, Intraub said she believes “this is something that is a very general aspect of perception. Whether we sample the world through eye movements or hand movements (when vision is not possible), the mind must be able to provide a coherent representation of a continuous world. Ignoring the spurious boundaries of a view and constructing the expected continuity allows the mind to provide a seamless representation for the observer.”

Intraub said that as you move your eyes to shift your focus, or as you move your hands to explore a new area, in a sense the mind gets there in advance of the senses.

Intraub said new research is under way in collaboration with other scientists to determine if neuroimaging can reveal the area of the brain associated with boundary extension, if eye movements determine the degree of constructive memory and if infants experience the same type of constructive error. She was recently awarded a National Institute of Mental Health subcontract from Brigham and Women's Hospital in Boston to join other vision researchers in studying scene perception.

Intraub’s work has drawn wide notice. A demonstration of boundary extension was selected to be part of an exhibit entitled “Human Memory” at the Exploratorium Science Museum in San Francisco from May 1998 through January 1999, and the demonstration also was selected for inclusion in a three-year national science museum tour that ends in 2003.

Intraub and colleague Carmela Gottesman, an assistant professor of cognitive psychology at the University of Oklahoma who earned a doctorate from UD, provided the touring exhibit with materials for teachers to use in bringing research to the classroom.

Article by Neil Thomas

|

|

[an error occurred while processing this directive]

|