|

11:15 a.m., Oct. 29, 2002--Since its entry into the national meteorological consciousness, it has become commonplace to lay the blame for any number of ills on El Niño, the name given a disruption of ocean and atmosphere in the tropical regions of the Pacific Ocean that, indeed, does have important consequences for weather around the globe.

Too much rain? Blame it on El Niño. Extended drought? Blame it on El Niño. Tough winter? Blame it on El Niño.

|

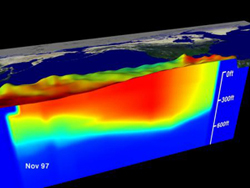

| This three-dimensional relief map of an El Niño in November 1997 shows a sea level rise along the Equator in the eastern Pacific Ocean of up to 34 centimeters with the red colors indicating an associated change in sea surface temperature of up to 5.4 degrees Celsius. The sea temperature below the surface illustrates how the thermocline (the boundary between warm and cold sea water at 20 degrees Celcius) is flattened out by El Niño. Source: NOAA |

Now, a University of Delaware researcher has come across another phenomenon for which people can blame El Niño–long days.

According to Xiao-Hai Yan, a professor of oceanography and co-director of the Center for Remote Sensing in UD’s College of Marine Studies, the strong westerly winds related to El Niño help produce warm and choppy waters in the Pacific Ocean, causing a slight imbalance in the Earth’s rotation rate that may slightly extend the length of the day.

Yan and other members of a nine-person research team analyzed satellite maps and found a correlation between elevated temperatures in the Western Pacific Warm Pool during years with strong El Niño currents and a tiny extension in the length of day, according to a paper accepted for publication by the American Geophysical Union Journal.

The researchers examined 30 years of water temperature data, from 1970-2000, and suggest that winds and warmed waters related to El Niño affect the balance of the Earth’s rotation and stir up the ocean water, resulting in a longer day by a few nanoseconds.

Their study is the first to link the behavior of a large water mass to the rotation of the planet.

|

| Xiao-Hai Yan, a professor of oceanography and co-director of the Center for Remote Sensing in UD’s College of Marine Studies |

Yan was joined in the study by researchers Yonghong Zhou, Dawei Zheng and Xinhao Liao, all of the Shanghai Astronomical Observatory and the United Center for Astrogeodynamics Research in Shanghai; Jiayi Pan, a postdoctoral fellow in UD’s College of Marine Studies; Mingqiang Fang and Ming-Xia He, both of the Ocean Remote Sensing Institute at the Ocean University of Qingdao, China; W. Timothy Liu, of the Jet Propulsion Laboratory at the California Institute of Technology; and Xiaoli Ding, of the Hong Kong Polytechnic University’s Department of Land Surveying and Geo-Informatics.

In addition to his position at UD, Yan is a National Presidential Faculty Fellow, an honor awarded by the White House and the National Science Foundation in 1994, and an honorary Cheung Kong Chair Professor at the Ocean University, which is sponsored by the Li Ka Shing Foundation of Hong Kong.

Article by Neil Thomas

|