Pavel Vidal Alejandro, Ph.D.

Center for the Study of the Cuban Economy

University of Havana, Cuba

|

Omar Everleny Pérez Villanueva, Ph.D.

Center for the Study of the Cuban Economy

University of havana, Cuba

|

Dr. Mario A. González-Corzo

Department of Economics

Lehman College

City University of New York

MARIO.GONZALEZ-CORZO@lehman.cuny.edu |

| ********************************************************************** |

In November 2010, the Cuban government published a 32-page document called “Lineamientos De La Política Económica y Social” [“Guidelines of Economic and Social Policies], which outlines the economic transformations approved in the Sixth Communist Party Congress last April 2011. The guidelines presented in this document expand the economic changes initiated by Raúl Castro in 2008. One of the major changes that already began is the transfer of State workers to the (emerging) private sector. This is the most transformative labor oriented economic adjustment implemented in Cuba so far and is a clear indicator of Cuba’s movement towards a reformed model of socialism in which the Non-State sector is likely to play a more significant economic role.

In October 2010 the Government authorized (or legalized) 178 self-employment activities. Self-employed workers are now able to directly negotiate the provision of their services to State-owned producers, thereby creating new contracting opportunities between the State and the (emerging) private sector. In addition, self-employed workers will be able to make contributions to the State-run social security fund, open bank accounts, obtain loans expand their operations, and will pay taxes on their income or earnings. In addition, self-employed workers and small-scale entrepreneurs will be permitted to hire third parties (i.e., other workers or employees), which expands the possibilities for the development of micro or small enterprises. At the same time, the Government announced plans to facilitate the creation of leasing arrangements (or contracts)that would allow current (State) employees to lease facilities such as cafeterias, barbershops, retail outlets, repair shops, etc. from the State and organize production cooperatives in other sectors of the economy besides agriculture.

The measures recognize the need to further expand the role of Non-State actors in the Cuban economy and explore alternative property forms and allocation and coordination mechanisms. To accomplish these goals, the State may assign a larger share of non-strategic economic activities to the Non-State sector, and even promote the creation and development of (privately-owned) Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs) in areas such as agriculture, housing, retail commerce, transportation, etc.

The transfer of State workers to the emerging private sector is also part of a series of economic policy transformations implemented by the Cuban government in response to the severe economic crisis confronted by island since 2008. As a response to this crisis, Cuba has also adopted a series of austerity measures focused on energy conservation, fiscal adjustment to reduce the ratio of the fiscal deficit to gross domestic product (GDP), transfers of non-productive State-owned lands to cooperatives and private producers, and the liberalization of consumption.

The labor adjustments and the economic changes present limitations, and if left unchanged, are likely to hinder Cuba’s prospects for successful economic reforms. The present article examines recent labor adjustments in Cuba and presents a balanced analysis of the new economic measures. This article demonstrates that while recent labor force and economic changes in Cuba represent a step in the right direction, these reform measures face a series of challenges that will require profound policy transformations and greater flexibility on the part of the Government.

- Principal Characteristics of the Cuban Labor Force

Economically Active Population (EAP)

At the end of 2009, Cuba had a working age population of 6,840,700, an economically active population (EAP) of 5,158,500, a labor force participation rate (LFPR) of 75.4%, and an unemployment rate of 1.7% (Table 1). Males represented 52.9% of the population of working age, and women represented 48.1%. In terms of the economically active population (EAP), men accounted for 61.7%, and women represented 38.3% (Table 1).

Like the majority of countries in the world, the labor force participation rate (LFPR) of Cuban men (88.4%) was higher to the labor force participation rate (LFPR) of their female counterparts (61%) (Table 1). With respect to the unemployment rate, the inverse relationship took place: the unemployment rate for males was 1.5% (or 13.3% below the national rate of 1.7%), while the unemployment rate for females was 2.0% (or 17.6% higher than the national rate (Table 1).

Table 1. Cuba: Economically Active Population (EAP), 2001; 2009 |

| |

Both Sexes |

Males |

Females |

| YEARS |

Working Age Population |

EAP |

Labor Force Participation (%) |

Working Age Population |

EAP |

Labor Force Participation (%) |

Working Age Population |

EAP |

Labor Force Participation (%) |

2001

2002

2004

2005

2006

2007

2008

2009

|

6,642.7

6,647.3

6,662.6

6,679.9

6,721.1

6,721.3

6,726.7

6,640.7 |

4,696.7

4,714.3

4,729.4

4,816.4

4,847.3

4,956.3

5,027.9

5,158.5 |

70.7

70.9

71.0

72.1

72.1

73.7

74.7

75.4 |

3,453.0

3,449.6

3,486.6

3,207.9

3,533.2

3,539.4

3,547.9

3,304.5

|

3,000.1

3,003.7

3,005.4

3,053.5

3,038.4

3,069.3

3,115.1

3,185.1 |

86.9

87.1

86.2

87.0

86.0

86.7

87.8

88.4

|

3,189.7

3,199.1

3,174.7

3,172.0

3,187.9

3,181.9

3,178.8

3,236.2 |

1,696.6

1,710.6

1,724.0

1,762.9

1,808.9

1,887.0

1,912.8

1,973.4 |

53.2

53.5

54.3

55.6

56.7

59.3

60.2

61.0 |

| |

Both Sexes |

Males |

Females |

| YEARS |

Employed |

Unemployed |

Unemployment Rate (%) |

Employed |

Unemployed |

Unemployment Rate (%) |

Employed |

Unemployed |

Unemployment Rate (%) |

2001

2002

2004

2005

2006

2007

2008

2009 |

4,505.1

4,558.2

4,641.7

4,722.5

4,754.6

4,867.7

4,948.2

5,072.4 |

191.6

156.1

87.7

93.9

92.7

88.6

79.7

86.1

|

4.1

3.3

1.9

1.9

1.9

1.8

1.6

1.7 |

2,906.3

2,926.8

2,955.7

2,998.5

2,985.8

3,016.0

3,073.0

3,138.3 |

93.8

76.9

49.7

55.0

52.6

53.3

42.0

46.8 |

3.1

2.6

1.7

1.8

1.7

1.7

1.3

1.5 |

1,598.8

1,631.4

1,686.0

1,724.0

1,768.8

1,851.7

1,875.2

1,934.1 |

97.8

79.2

38.0

38.9

40.1

35.3

37.7

39.3

|

5.8

4.6

2.2

2.2

2.2

1.9

2.0

2.0 |

Sources: Oficina Nacional de Estadísticas (ONE), Anuario Estadístico de Cuba (AEC). 2009, 2010, and authors' calculations |

Employment by Industry

As Table 2 demonstrates, the majority of Cuban workers are employed in the agricultural sector (17.8%), followed by education (13.7%), public health, social assistance, sports and tourism (13.2%), construction (4.6%), personal, social and communal services (4.3%), art and culture (2.7%), and science and technology (0.8%).

In terms of growth, it can be noted that between 2008 and 2009 the number of workers grew in some sectors of the economy such as industry (23%), education (5.7%), public health, social assistance, sports and tourism (5.2%), and culture and art (11.5%). During the same period, employment contracted in other areas such as construction (-4.3%), agriculture (-1.9%), and science and technology (-0.8%) (Table 2).

|

|

|

|

|

Table 2. Cuba: Employed persons by sector, 2008-2009, thousands

|

| |

2008 |

2009 |

Change |

Percentage

Change |

| Employed persons |

4,948.2 |

5,072.4 |

124.2 |

2.5% |

| Females |

1,875.2 |

1,934.1 |

58.9 |

3.1% |

| Males |

3,073.0 |

3,138.3 |

65.3 |

2.1% |

| Industry/Manufacturing |

543.1 |

667.8 |

124.7 |

23.0% |

| Construction |

245.2 |

234.6 |

-10.6 |

-4.3% |

| Agriculture |

919.1 |

902.0 |

-17.1 |

-1.9% |

| Personal, Social, and Communal Services |

207.8 |

216.1 |

8.3 |

4.0% |

| Science and Technology |

39.6 |

39.3 |

-0.3 |

-0.8% |

| Education |

658.1 |

695.6 |

37.5 |

5.7% |

| Public Health, Social Assistance, Sports, and Tourism |

638.3 |

671.2 |

32.9 |

5.2% |

| Art and Culture |

123.7 |

137.9 |

14.2 |

11.5% |

Sources: Oficina Nacional de Estadísticas (ONE), Anuario Estadístico de Cuba (AEC). 2009,2010 and authors' calculations |

|

Employment by Sector

The majority of Cuban workers (83%) are employed by the State sector; the rest work in cooperatives (4.8%) and the emerging private sector (12.2%). There were an estimated 146,100 (legally-registered) self-employed workers (cuentapropistas or trabajadores por cuenta propia) in Cuba at the end of 2008, accounting for 2.8% of the economically active population (EAP), but close to 17% of all workers in the Non-State sector (Table 3).

Table 3. Cuba: Employed Persons by Sector, 2005-2008 |

| |

2005 |

2006 |

2007 |

2008 |

Employed Persons |

4,722.50 |

4,754.60 |

4,867.70 |

4,948.20 |

| Cooperative sector |

271.3 |

257 |

242.1 |

233.8 |

| Private sector |

665.6 |

609 |

589.5 |

602.1 |

| Self-employed workers |

169.4 |

152.6 |

438.4 |

141.6 |

Ratios by Sector

|

| State Sector |

81% |

82% |

83% |

83% |

| Non-State Sector |

19% |

18% |

17% |

17% |

Sources: Oficina Nacional de Estadísticas (ONE), Anuario Estadístico de Cuba (AEC). 2009, 2010 and authors' calculations |

|

Educational Attainment

As a result of substantial investments in training and education, Cuba has a highly educated and qualified labor force. Table 4 shows that 14.5% of Cuban workers have a college/university degree or higher, 50.6% are considered technicians/specialists in their respective fields or professions, and 26.9% have at least received some form of training at institutions of higher learning. Females enjoy higher levels of educational attainment compared to their male counterparts; 19% hold college/university degrees, compared to 11.6% of males.

Table 4: Cuba: Educational Level by Gender

|

| |

2003 |

2004 |

2005 |

2006 |

2007 |

2008 |

| |

Both Sexes |

Total |

4,716.6 |

4,729.4 |

4,816.4 |

4,847.3 |

4,956.3 |

5,027.9 |

| Primary school or lower |

598.4 |

567.5 |

514.7 |

478.1 |

396.7 |

401.0 |

| Secondary |

1,425.6 |

1,409.5 |

1,443.9 |

1,346.2 |

1,353.9 |

1,353.4 |

| Middle |

2,032.4 |

2,085.3 |

2,195.7 |

2,357.3 |

2,476.2 |

2,545.9 |

| Superior |

660.2 |

667.1 |

662.1 |

665.8 |

729.5 |

727.6 |

| |

Males |

Total |

2,997.0 |

3,005.4 |

3053.5 |

3,053.5 |

3,069.3 |

3,115.1 |

| Primary school or lower |

468.7 |

437.0 |

398.9 |

398.9 |

314.0 |

315.3 |

| Secondary |

1,043.2 |

1,028.0 |

1065.9 |

1,065.9 |

982.0 |

978.9 |

| Middle |

1,148.1 |

1,199.1 |

1247.6 |

1,247.6 |

1,405.4 |

1,459.2 |

| Superior |

337.0 |

341.3 |

341.1 |

341.1 |

367.9 |

361.7 |

| |

Females |

Total |

1,719.6 |

1,724.0 |

1762.9 |

1,808.9 |

1,887.0 |

1,912.8 |

| Primary school or lower |

129.7 |

130.5 |

115.8 |

107.6 |

82.7 |

85.7 |

| Secondary |

382.4 |

381.5 |

378.0 |

365.5 |

371.9 |

374.5 |

| Middle |

884.3 |

886.2 |

948.1 |

1,006.5 |

1,070.8 |

1,086.7 |

| Superior |

323.2 |

325.8 |

321.0 |

329.3 |

361.6 |

365.9 |

Sources: Oficina Nacional de Estadísticas (ONE), Anuario Estadístico de Cuba (AEC). 2009, 2010 and authors' calculations |

|

Wages and salaries

In 2009, the average monthly salary in Cuba was 429 pesos (CUP); in nominal terms this represents an increase of 51% compared to 2004. The areas of the economy with the highest monthly nominal wages in 2009 were mining (537 pesos), retail, restaurants, and hotels (534 pesos), construction (531 pesos), utilities (530 pesos), and finance, insurance and real eState (502 pesos). At the prevailing exchange rate of 25 Cuban pesos (CUP) per convertible peso (CUC), the average monthly salary (in 2009) of 429 pesos was the equivalent of 17.16 CUC or $18.53 (USD), rendering the insufficiency of salaries (and for that matter pensions) as one of the most serious challenges confronting the Cuban economy at the present time.

Table 5. Cuba: Median Monthly Salary in State and Mixed Enterprises, 2004-2009 pesos |

Industry or Sector |

2004 |

2005 |

2006 |

2007 |

2008 |

2009 |

Total |

284 |

330 |

387 |

408 |

415 |

429 |

| Agriculture, fishing, and hunting |

297 |

332 |

387 |

420 |

444 |

483 |

| Mining |

353 |

407 |

540 |

544 |

562 |

537 |

| Industry/Manufacturing |

290 |

338 |

404 |

433 |

430 |

449 |

| Electricity, Gas, and Water |

339 |

398 |

496 |

508 |

517 |

530 |

| Construction |

349 |

400 |

478 |

497 |

522 |

531 |

| Retail Commerce |

230 |

280 |

334 |

353 |

365 |

534 |

| Transportation, Warehousing, and Communications |

295 |

331 |

406 |

418 |

427 |

430 |

| Finace, Insurance, Real Estate, and Services |

332 |

402 |

477 |

493 |

445 |

502 |

| Personal, Social, and Communal Services |

285 |

331 |

378 |

398 |

385 |

418 |

Sources: Oficina Nacional de Estadísticas (ONE), Anuario Estadístico de Cuba (AEC). 2009, 2010 and authors' calculations |

|

- Raúl Castro´s Economic Changes

Between 2008 and 2009, Raúl Castro implemented some (limited) structural changes; some of these measures produced immediate positive results, while others highlighted the need for further policy transformations. The consumption of selected goods and services such as personal computers, DVD players, cellular telephones and access to tourism and entertainment facilities, was liberalized in 2008.

While the liberalization of consumption represents a positive step to correct existing imbalances between global demand and supply, the rigidity of wages (in the labor market) and prices (in the goods producing, or output, sector), combined with the reduced purchasing power of a significant portion of Cuban households, limits the economics effects of these measures. At the present time, over 80% of the Cuban workers are employed by the State sector, where real wages and salaries remain notably below the levels reported in 1989, the year before the onset of the “Special Period.”

The insufficiency of salaries (and pensions) in Cuba limits consumers’ access to recently liberalized products and services, constraints the emerging private sector’s ability to earn income and profits to attract new entrants, contributes to the country’s dependency on remittances and other transfers and limits economic growth. Therefore, it seems logical and rational to combine the liberalization of consumption with the introduction of policy measures to establish and permit expanded employment options; this naturally requires a growing economic role for the Non-State sector and could act as a catalyst to stimulate foreign and domestic investment in sectors of the economy where output is primarily oriented towards domestic consumption.

The liberalization of selected rationed goods and services is another critical element of Cuba’s recent structural transformation. In recent years, the State has gradually liberalized the distribution and consumption of important rationed good such as potatoes, lentils, and chocolate powder to mention a few. The liberalization of selected goods and services, previously offered through the rationing system serves as a tool to adjust the country’s fiscal balance.

The transfer of idle State-owned lands to private producers and cooperatives after the approval of Decree Law No.159 (in 2008) represents another significant structural change. According to official estimates more than 50% of State-owned agricultural land sits idle; Cuba spends close to $2 billion USD to satisfy more than 80% of its domestic food consumption, which is primarily imported from the US. As of December 2009, more than 920,000 hectares or 54% (of idle State-owned lands) have been redirected to more than 100,000 applicants.

According to Nova (2009), despite these positive measures, Cuban agriculture remains constrained by a series of endogenous and exogenous factors such as: the relatively short period of duration of the leases extended to agricultural producers by the State (10 years), restrictions on the type of operational infrastructure (e.g., housing, warehousing/storage facilities, etc.) that private producers or cooperatives can build on agricultural land leased from the State.

Mesa-Lago (2010a) adds that the leases granted by the State have relatively short terms: 10 years in the case of individuals and in 20 years in the case of cooperatives. Second, the lease agreement between the State (the lessor) and the individual farmer or cooperative (the lessees) can be cancelled (by the State) if the lessee fails to fulfill and of the terms of its contract (with the State). Third, Decree-Law No. 259 (2008) does not clearly articulate if there is any restitution by the State for investments or expenditures made by producers on repairs and infrastructure if the contract between the two parties is cancelled. Finally, the income earned by agricultural producers is subject to relatively burdensome taxes, which, as indicated before, discourage work and production.

Cuba’s rural population represents a relatively small share (25%) of the total, tends to be older, and disproportionately relies on labor intensive production techniques; the State has limited resources to invest in larger-scale, capital-intensive farming, and the private sector’s relatively small share of the country’s arable land limits its capacity to achieve scale economies by producing more output at lower average costs.

Cuba’s agricultural sector also remains constrained by the centralized nature of internal factor and output markets. Inputs or factors of production remain heavily controlled and subsidized by the State, and output markets, particularly the agricultural supply chain, are for the most part operated by the State-run procurement agency, Acopio. This centralized (output/distribution) coordination mechanism functions like the country’s de facto agricultural central planning board (CPB) by assigning the prices that the State will pay for agricultural output, determining the type of products allowed, and regulating the relationship or interactions between agricultural producers and consumers.

In addition to the structural changes previously described, the Cuban government has implemented several institutional changes since 2008. In 2008 speech president Raúl Castro indicated that “It is necessary and decisive to develop stronger political institutions, mass organizations, social organizations and youth organizations…the larger the difficulties, the more order and discipline are required; and to accomplish that it is vital to reinforce our institutions, respect for the laws and norms established by ourselves (Castro, 2008). The institutional changes set in motion since 2008 have resulted in the reorganization and consolidation of several ministries, the restructuring of the council of State and the creation of the creation of the General Comptroller of the Republic. These measures aim to streamline the State’s administrative apparatus, improve operational efficiency, reduce or eliminate excessive bureaucratic practices and procedures, eliminate existing procedural redundancies and functional overlaps, and improve the management and control of fiscal resources (Vidal, 2010).

In early 2008, the Ministry of Foreign Trade and the Ministry of Foreign Investment were consolidated; a few months later, the Ministries of the Fishing Industry and the Food Industry followed the same path. The operations of the once extensive Council of State were transferred to key ministries to eliminate existing redundancies and streamline operations. In 2009 the Office of the General Comptroller of the Republic was established to monitor and supervise the country’s political, administrative, and economic processes and institutions and spearhead the government’s efforts to strengthen its institutions, improve the management and allocation of its scarce fiscal resources and fight corruption.

Cuba’s institutional reorganization since 2008 has also shifted the balance of (economic) power from the Central Bank to the Ministry of the Economy and Planning (MEP), and the replacement of ministries and key figures in the Central Bank and almost all the Ministers. For the most part, the recently appointed ministries and administrative personnel responsible for the country’s economic policies are government-career officials, with a strong record and a proven ability to implement the managerial and policy measures necessary to move the institutionalization process forward and exert greater control and fiscal discipline.

It was confirmed in 2010 that the Cuban economy was entering a new period of economic reforms, officially label as an “update of the economic model." The “Draft Guidelines for the Economic and Social Policy” was the subject of a public consultation and discussed in a wide range of forums, by mid April 2011, at the Sixth Congress of the Cuban Communist Party (PCC). President Raul Castro has specified that the goal of the reform is to "perfect socialism." In the 1990s, as a response to the economic crisis resulting from the collapse of the Eastern European Socialist Bloc and the disintegration of the Soviet Union, Cuba embarked on a process of economic reforms, which were halted in the first decade of this century once the country’s economy was able to recover and Cuba due to the diversification of trading partners, improved international relations, the influx of remittances, the expansion of tourism, and Cuba’s growing economic ties with Venezuela.. At the present time, Cuban authorities have insisted that unlike the policy transformations of the 1990s, the economic reform measures currently underway are permanent and structural in nature. The Sixth Party Congress and the Guideline of Economic and Social Policies represent another move towards the “institutionalist” style of governance often praised by President Raúl Castro Ruz, and constitute an essential tool to help him to reach consensus and political support with regards to the pace and scope of economic reforms.

After more than five (5) decades of centralized planning, Cuba’s labor force has been affected by relatively low worker productivity, the predominance of the State sector as the country’s principal employer, lack of adequate inputs, access to obsolete technologies and production techniques, the absence of modern managerial systems and practices, and the traditional rigidities commonly associated with centrally-planned economies (CPEs).

To confront these deficiencies, and as part of a concerted effort to transform the Cuban economic model, on September 13, 2010 the State-affiliated national labor federation (Central de Trabajadores de Cuba, CTC) announced a plan to reduce the number of workers employed by the State by 500,000 between October 4, 2010 and March, 2011 (the initial schedule is delayed and is supposed to start by January 2011. The displacement of these half-million workers represents the first stage of a multi-tiered strategy to reduce the number of workers employed by the State sector by 1,000,000 (or 19.4%).

Displaced State workers will be relocated to sectors with deficits (i.e. insufficient workers) such as agriculture, construction, law enforcement, education, and industry. Most of the reductions will apply to “bureaucratic functions” such as management and administration, and their primary goal is to increase the share of “productive workers” (or “blue collar” workers) to 80% of the workforce in State-owned enterprises (SOEs) and ministries.

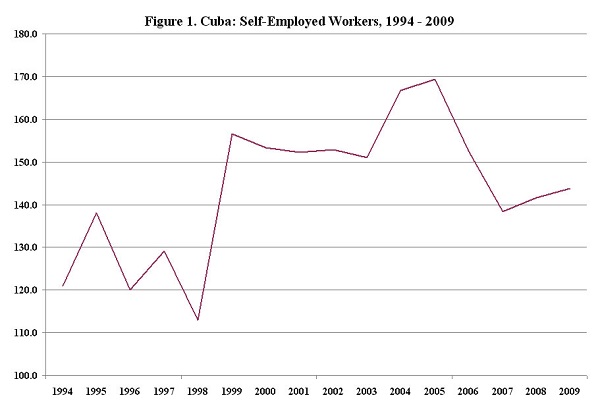

To support the labor adjustment the Government will issue new licenses for self-employed workers in areas in which it can supply essential inputs. Self-employment expanded significantly after the approval of Decree-Law No. 141 in 1993. Figures from the National Statistics Office (ONE) show that in the 1980s the number of self-employed workers was around 50,000. In 1994, a year after the approval of Decree No. 141 (1993), the number of self-employed workers reached an estimated 121,000. Figure 1 shows the erratic nature of self-employment in Cuba.

Sources: Prepared by the authors based upon the Cuban National Statistic Office data.

Self-Employment Statistics |

|

TPCP |

|

| 1994 |

121.0 |

|

| 1995 |

138.1 |

14% |

| 1996 |

120.0 |

-13% |

| 1997 |

129.2 |

8% |

| 1998 |

112.9 |

-13% |

| 1999 |

156.6 |

39% |

| 2000 |

153.3 |

-2% |

| 2001 |

152.3 |

-1% |

| 2002 |

152.9 |

0% |

| 2003 |

151.0 |

-1% |

| 2004 |

166.7 |

10% |

| 2005 |

169.4 |

2% |

| 2006 |

152.6 |

-10% |

| 2007 |

138.4 |

-9% |

| 2008 |

141.6 |

2% |

| 2009 |

143.8 |

2% |

|

In 1999, there were an estimated 157,000 self-employed workers in Cuba. Between 2000 and 2003, the number of self-employed workers stagnated, as few licenses were issued (or approved). Self-employment reached a peak of approximately 170,000 workers in 2005, but declined to 138,000 in 2007, reaching the same amount reported in 1995. At the end of 2009, the number of (legally-registered) self-employed workers reached an estimated 146,100, well below the peak recorded in 2005 (170,000).

Overall, self-employment has had a positive impact on the supply of consumer goods and services, particularly in areas such as food preparation and sales and private transportation. For some Cuban households, self-employment represents an alternative source of income (or earnings) to supplement insufficient pensions and State wages, while serving as a source of tax revenue for the State. As Figure 1 indicates, however, self-employment has fluctuated quite dramatically since it was fist authorized en masse in the 1990s; primarily as a result of ambivalent State policies towards this dynamic sector of the Cuban economy, a significant share of self-employed workers have been forced to operate in the informal (or second) economy. The growth of self-employment has been constrained by a larger number of prohibitions, some of which now seem to be addressed by the government.

As a sign of the government’s “new direction” with regards to self-employment, Cuba’s official newspaper, Granma, indicated that “we should stay away from those conceptions that condemn the work of self-employment and stigmatize those that decide to submerge themselves in [these type of activities]” (Granma, 2010). In late September 2010, Granma published list of 178 self-employment activities that will be permitted starting in October 2010. The new regulations regarding self-employment include several new occupational categories that were not in effect, or were eliminated, during the 1990s and in the earlier part of this century; they represent a more flexible regulatory framework, which allows self-employed workers to:

-

Have access to bank credit and financing

-

Hire third parties as workers or employees, which essentially turns the small-scale sole proprietorships operated by self-employed workers into microenterprises capable of operating at a greater scale

-

Rent premises and assets from the State and other citizens

-

Engage in “dual” (or multiple) employment (pluriempleo); work in both the State and Non-State sectors

-

Rent/lease/sublet residential property (or rooms within such property) on an hourly, daily, monthly, or annual basis, including property assigned or maintained by the State

-

Rent/lease/sublet residential property and/or automobiles to persons residing overseas, or those leaving the country temporarily for more than 3 months (using a self-appointed representative or intermediary)

-

Operate privately-owned restaurants (paladares), which can have a maximum of 50 seats (instead of the 12 seats previously allowed), and sell foods containing potatoes, seafood, and beef.

|

Anecdotal evidence suggests that some of these (newly-authorized) activities have already been taking place informally, and at the present it is unclear if all of them will be formally legalized. However, if formally approved or legalized, these measures should contribute to the expansion of self-employment in Cuba. The authorization of these activities, along with the flexibility to directly sell output to State-owned enterprises (SOEs) should serve as an economic incentive to promote the growth, allowing the emerging private sector to absorb a portion of the workers that will be released from the State sector in the near future.

The Cuban government has also authorized leasing agreements as a preliminary experiment the expansion of Non-State economic actors in sectors such as transportation (i.e. taxis, trucks, etc.) and selected areas of retail commerce (e.g. barbershops, beauty, salons, etc.) There are also plans to selected, small and medium sized, State enterprises into cooperatives.

The principal reasons given for the reduction of workers in Cuba’s State sector were the un-sustainability of the current system, under which the majority of the economically active population (83%) works in the State sector, the need to improve worker productivity, the heavy fiscal burden that unproductive workers represent for the State, and the need to increase output, improve total factor productivity (TFP), and achieve higher levels of economic efficiency.

Over the years, Cuba’s mostly State-employed work force has become an increasingly unsustainable burden for the State. Generous State subsidies mostly in the form of free social services (e.g., health care and education), subsidized workplace meals, paid vacations, workplace-sponsored distributions of consumer goods and along with other direct and indirect transfers, including goods provided through the rationing system, have increased the State’s outlays (or expenditures), and prompted the development of policy measures to transform the relationship between Cuban workers and the socialist State.

Expenditures in education increased 127.5% from 3.297 billion pesos in 2003 to 7.503 billion pesos in 2008 (ONE, 2010a). Health care expenditures grew even faster during the same period, increasing by 254.5% from 2.028 billion pesos in 2003 to 7.189 billion in 2008 (ONE, 2010a). Expenditures on social security and on subsidies to the rationing system have also grown quite significantly. In 2003, Cuba spent 2.054 billion pesos on social security (which mainly includes pensions and payments to disabled persons). This figure increased 114.2% to 4.400 billion pesos in 2008 (ONE, 2010a). Similarly, subsidies to the rationing system grew from 1.987 billion pesos in 2003 to 2.212 billion pesos in 2008, representing an increase of 11.3% during this period (ONE, 2010a). As a share of total expenditures in 2008, education represented 16.2%, health care 15.5%, social security 9.5%, and subsidies to the rationing system 4.8% (ONE, 2010a).

The insufficiency (in real terms) of salaries and pensions in Cuba is one of the main economic challenges to be addressed in the forthcoming Sixth Party Congress. According to the “Guidelines” document, one of Cuba’s top economic priorities will be to strengthen/fortify the role of salaries (and wages) in society, while addressing related issues such as the linkages between compensation/remuneration and productivity and the (reduced) purchasing power of salaries (and wages).

At the present time, it can be reasonably expected that the labor adjustments introduced in 2010 will favor wage increases in State sector in several ways:

-

The reduction of the fiscal deficit may provide the State with the necessary resources to raise wages, and use wages (or “material incentives”) to stimulate higher labor productivity.

-

The implementation and development of more flexible labor contracts in the State sector, particularly in cases in which compensation is directly linked with results, is likely to contribute to improved enterprise profitability; combined with the elimination of any excess capacity, this measure will likely increase the financial resources that enterprises might have at their disposal to distribute among their workers.

-

The elimination of existing policies that guarantee full employment in the State sector and reduction of transfers and subsidies (e.g. free meals at work places, and other benefits) are expected to improve discipline and labor profitability, which can serve as the basis for calibrated wage increases.

The notion that wage increases must be directly connected with labor productivity is a common denominator between the labor reform measures implemented since 2008, the labor adjustments announced in October 2010 and the “Guidelines”.

- Limitations of the Labor Adjustments

The experiences of other countries that have transitioned from the classical socialist model to its reformed version suggests that these measures tend to improve economic efficiency, increase total factor productivity (TFP), and generally have a positive effect on household income, consumption, and living standards.

In the case of Cuba, despite these potential benefits, these economic measures face several constraints and limitations such as:

-

The majority of State workers are employed in service-related occupations: few have practical (i.e. fungible) experience in areas in which the emerging non-State sector is likely to play a larger economic role, such as: agriculture, construction, and low-scale, labor- intensive manufacturing;

-

The new measures lack the provisions necessary to create (or develop) fully functioning input markets;

-

The relative stagnation currently affecting the Cuban economy represents another obstacle for the creation and expansion of microenterprises. In order to grow, and increase its demand for factors of production and other inputs, the emerging private sector needs a healthy economy; at the same time, in order to increase the supply of goods and services to this sector, the State, which still remains as the principal allocation and coordination mechanism, needs the reassurance that there will indeed be demand (from the emerging private sector) for the goods and services that it plans to provide. Regardless of the sequence of event, and whether we assume that supply (in order to exist) necessitates demand, or conversely demand will ultimately drive supply, one thing remains for sure: the lackluster growth experienced by the Cuban economy in the aftermath of the global financial crisis is one of the major limitations confronted by the emerging private sector.

-

The production possibilities of Non-State economic actors, whether self employed or part of a cooperative, are constrained by their limited access to diversified sources of credit and financial capital; and

-

Output by the Non-State sector is subject to onerous taxes, which serve as a disincentive to produce more and will probably force a notable portion of non-State producers into the informal sector.

As Mesa-Lago (2010b) indicates, the onerous tax provisions associated with the new measures represent a serious limitation. In terms of personal income taxes, the first 5,000 pesos (CUP) of annual income are exempt, but any income (earnings) above 5,000 pesos (CUP) is subject to taxes, depending on the type of activity/occupation. For example, food outlets/restaurants/food preparation face a tax rate of 40%, self-employed workers engaged in activities related to transportation (passengers and/or merchandise) are required to pay a 30% tax; construction/manufacturing/art workers, personal services, technical service, maintenance workers, artists pay 25%; those engaged in renting apartments or houses pay 20%, and those that participate in other activities pay 10%. According to the new measures, self-employed workers must contribute 25% of monthly income to social security; those that employ a third party are required to pay a 25% tax on the utilization of labor, and sales taxes are established at 10% of gross revenues.

As part of the recently announced labor reforms the Cuban State has reduced unemployment insurance provisions. In the past unemployed or displaced workers were entitled to 100% of their salaries (or compensation) for an unlimited period of time, until the State was able to place them in a new job or position. By contrast, the new measures stipulate that unemployed or displaced State workers with at least 10 years of service will receive 100% if their base salary for a month: anyone unable to find an alternative source of employment (in the non-State sector) after the first month will receive 60% of their base salary for another month, if he or she has between 25 and 30 years of service, and for 5 months, provided that he or she has more than 30 years of service. The new policies also eliminate school enrollment, or training programs as a substitute for employment. The new measures eliminate the generous unemployment benefits of the past, and their related distortions, but are very strict when compared to unemployment insurance programs in selected countries in Latin American and the Caribbean (Mesa-Lago, 2010b).

Another limitation of the new labor adjustments results from the limited capacity of the Non-State to absorb the large number of workers (1,000,000) that will be released from the State sector. As indicated before, in 2009, the majority of Cuban workers (83%) were employed by the State, and at the present time the Non-State sector lacks the capacity to expand at the rate necessary to absorb the first cohort of displaced State workers in such a short period of time. Vidal and Pérez Villanueva (2010) expect the number of self-employed workers to exceed the peak recorded in 2005 (169,400), and consider that the newly-authorized or 178 self employment activities or occupations will not be sufficient to absorb the vast number of workers that will be released from the State sector.

One of the expected outcomes of the recently announced labor reforms in Cuba is the displacement of highly educated (or qualified) workers from the State sector to emerging occupations in the Non-State sector. As Mesa Lago (2010b) and Vidal and Pérez Villanueva (2010) indicate, the majority of these self employment occupations (or activities) are less knowledge intensive, and do not leverage the investment in education that Cuba has made for decades. Underutilized, overqualified, highly-educated workers are likely to represent a significant share of the newly self-employed, resulting in a monumental misallocation of one of Cuba’s most valuable resources: its highly-educated and resourceful people.

In order to be successful, the new labor-oriented measures will require the development of well-functioning input and output markets. This will require the establishment and development of regulated structures and institutions that would allow markets to facilitate the process of price discovery and provide participants with price signals to ensure Pareto optimal outcomes. Efficient input and output markets will also require well functioning credit and financial markets capable of mobilizing credit and financial capital, transferring risk, and rewarding individual effort and initiatives.

In April 2011, the Cuban announced that some 200,000 self-employment licenses had been granted (or authorized) since the initial implementation of the labor adjustments on October 2010. This represents a significant increase in the number of legally-registered self-employed workers, and almost a 100% increase with respect to the historical average since the 1990s. However, these figures do not include the number of self-employment licenses returned by formerly self-employed workers to the State during this period.

Official confirmation that the original plan to transfer close to 20% of Cuba’s economically active population (EAP) from the State sector to the emerging private sector through the expansion of legally-registered self-employment has been drastically scaled back, due to various difficulties, also represents an obstacle for the labor adjustments announced in October 2010. The initial plan called for the reduction of an estimated 500,000 State workers starting in October 2010, but was later postponed to the first quarter of 2011. More recently it has been restructured to allow greater flexibility and a more gradual implementation.

The plan (or strategy) as originally announced and envisioned appears to not have taken into account the wide range of challenges and difficulties associated with the scope and scale of such wide ranging adjustments and transformations, after more than five decades of centralized planning and the prominence of State sector employment. The relatively short period of time during which the announced labor adjustments were expected to take place and their overall disruptive impact and consequences created difficulties for the implementation of the original plan in terms of feasibility and execution; and the plan, as originally conceived, did not anticipate the fact that the legal spaces created (by the State) to facilitate the expansion of self-employment as an alternative to employment in the State sector would be for the most part occupied (or claimed) by retirees or individuals already operating in the informal economy without any previous or existing links to employment in State enterprises, thereby placing a serious constraint on the ability of former State workers to engage in legal self-employment activities. One interesting statistic that reflects the magnitude of this challenge is that more than 60% of newly-licensed self-employed workers are retired persons or individuals already working (informally) in the emerging private sector.

The acceptance and recognition of a greater economic role for the non-State sector represents one of most significant changes implemented by Raúl Castro since officially assuming Cuba’s presidency on February 24, 2008, and a fundamental step in the potential path towards market socialism.

The expansion of employment options in the Non-State sector in particular, if carried out as announced through the creation of additional forms of self-employment, the expansion of cooperatives and the creation of privately owned Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs), can result in additional benefits through the multiplier effect. In addition to contributing to increased tax revenues for the State, measures to expand the size and scope of the (emerging) private sector represent a viable solution to address the insufficiency of salaries and pensions in Cuba by providing legal mechanisms to supplement household incomes.

Ultimately, over time, the liberalization of rationed goods and services combined with the labor adjustment and the further liberalization of consumption, will contribute to fiscal equilibrium, positive externalities, and improvements in economic efficiency and total factor productivity (TFP). The potential liberalization of the housing and transportation sectors in the near future will likely provide additional mechanisms to expand the role of Non-State actors in the economy.

The labor adjustment and the expansion of the Non-State sector would require additional or complementary policy changes. Economic decentralization, price liberalization and monetary (or currency) unification are essential requirements to reactivate the Cuban economy by applying economic incentives, improving total factor productivity (TFP), attracting foreign investment, and achieving higher levels of economic efficiency. At some point in the near future, enterprises across all sectors of the Cuban economy should be allowed to rely on the forces of supply and demand to set prices and allocate inputs and output more efficiently. This process will require a careful analysis of existing monopolistic structures and increased accountability and transparency. Social policies must be able to adapt to this new socioeconomic scenario and address the impact of the labor adjustments and future economic changes. The experiences of other countries that have transitioned from the classical socialist model to its reformed version demonstrate that the process of economic reforms is likely to encounter resistance even if conducted within the framework or boundaries of socialism. The process of economic transformations is likely to encounter some resistance, not only in the economic front, but also from political and institutional perspectives.

Castro, R. (2008), Speech in the Cuban National Assembly, February, Havana.

Granma, (2010) “Trabajo por cuenta propia, mucho más que una alternativa”, September 24, Havana,

Mesa-Lago, C. (2010a). La crisis economica en Cuba. Convivencia. Retrieved November 15, 2010 from http://convivenciacuba.es/content/view/538/56/

Mesa-Lago, C. (2010b). Convirtiendo el desempleo oculto en visible en Cuba: ¿Podrán emplearse 1 millón de trabajadores despedidos? Espacio Laical Digital. Año VI, No. 24. (Octubre-Diciembre). Retrived November 26, 2010 from http://espaciolaical.org/contens/24/5966.pdf

Nova, A. (2009). Agricultura. In Miradas a la Economía Cubana (pp. 45 -98). Editorial Caminos. La Habana.

Oficina Nacional de Estadísticas [ONE]. (2010a). Anuario Estadístico de Cuba [AEC]. (2009). La Habana, Cuba.

Oficina Nacional de Estadísticas [ONE]. (2010a). Panorama Económico y Social (2009). La Habana, Cuba.

Lineamientos de Política Económica y Social. (2011). Retrieved May 27 from http://www.granma.cubaweb.cu/secciones/6to-congreso-pcc/Folleto%20Lineamientos%20VI%20Cong.pdf

Vidal, P. (2010). Los cambios estructurales e institucionales. Espacio Laical Digital. Año VI, No. 21. (Enero-Marzo). Retrived October 12, 2010 fromhttp://espaciolaical.org/contens/21/5760.pdf

Vidal, P. & Pérez Villanueva, O. (2010). Se extiende el cuentapropismo en Cuba. Espacio Laical Digital. Año VI, No. 24. (Octubre-Diciembre). Retrived November 26, 2010 from http://espaciolaical.org/contens/24/5358.pdf

|