|

|

Expedition

Expedition | People

|

Log - August-9-2003

by Gerhard Behrens and Robert McCarthy

Previous | Next

What color would you be?

Robert McCarthy |

|

Last night, after our daily science meeting in the conference room, we were treated to a video. It wasn’t Hollywood’s new release, but it was captivating. It was from an underwater video camera. The video camera was used by the divers to spot a likely dive site for retrieving clams. They actually could see the siphons of the clams while sitting on the boat. This proved helpful in harvesting some clams. The visibility was greater than I had expected, but I was reminded about how drab and blue everything looks underwater. There were large kelp beds, sea urchins, brittle stars, starfish, and plenty of plant life at depths of 30 to 70 feet. So the question is, what color plant would you be if you wanted to thrive in these waters if you needed sunlight to grow? |

| The answer is surprising. But first let’s investigate how light is attenuated with depth. One of the first colors to be filtered out is red. Red has the longest wavelength, and it is absorbed first; then comes orange, followed by yellow, green and finally blue. Red light penetrates to about 10 feet, while the blues go down to the photic zone (the depth of light penetration) which is affected by such factors as sun height in the sky, turbidity of the water column, productivity, nutrients, etc. Since blue light travels the deepest, you would think that the plant life would be blue. That would be incorrect! |

|

|

These plants are brightly colored reds, orange-yellows, and greens. Why are they brightly colored, and why do they look so drab? The answer is how we see color. We see something as red because the red light reflects off the object. All the other colors are absorbed. And that’s the answer! If you’re a plant, you want to absorb the available sunlight, not reflect it. For example, if you were a blue plant, you would reflect the blue wavelengths, not absorb them. Hence you would not absorb any light and you wouldn’t be able to grow. I can remember watching Jacques Cousteau shows on TV as a kid, and being amazed at how different the coral reef looked when they dove at night. During the day dives, the reef appeared washed out and drab. But on a night dive, the reef took on a colorful, almost magical appearance. The bright, underwater strobe-lights the divers took down illuminated the objects that were being filmed without the loss of the red wavelengths (the distance from the strobe to the subject was too short for appreciable absorption). Here, a night dive is the same as a day dive, since the sun hasn’t set in almost 2 weeks. Again that’s another story for another day. The pictures today were taken off the TV while I was watching the video, courtesy of Mary O’Brien. Thanks to her and to the divers again, who continue to do their job with enthusiasm. Hats off! |

|

|

|

|

Anything out there?

Gerhard Behrens |

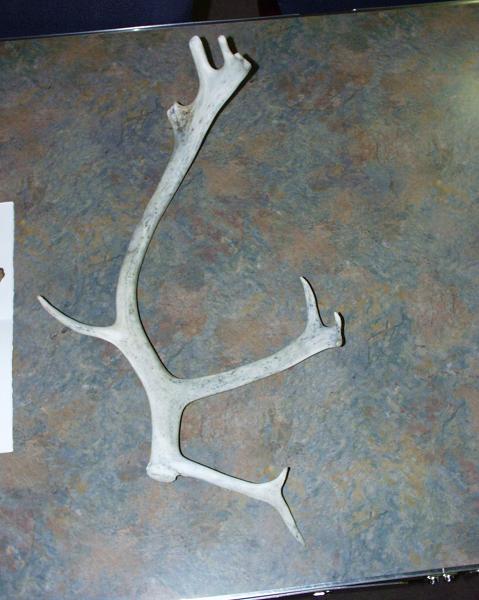

Caribou antlers found on the northeast tip of Ellesmere Island. |

My hometown newspaper, the Corvallis Gazette-Times, asked me what I found most surprising about this cruise. One surprise for me is how barren the land and sea seems. I have seen gorgeous mountains, picturesque seas, magnificent glaciers, incredible icebergs, and fabulous ice floes. Since we are unable to get off the ship, I have not seen the wildlife or plant life that I had read about. |

| But there is life out there! 35 kinds of mammals live on the land in this far north. Some large mammals like Caribou (or reindeer), moose, and musk ox graze on grasses, mosses, lichens, sedges, berries, and willows. The musk ox has a thick undercoating of fur that neither water nor cold can go through. Brown bears and polar bears are the largest predators. The wolf is the most widespread predator, hunting in packs to attack the smallest or weakest animal in a caribou or musk ox herd. |

The musk ox is a powerful mammal, well built the harsh life of the Arctic. |

The wolf is a successful pack hunter. |

There are plenty of smaller mammals in the food chain: voles (like mice), ground squirrels, weasels, and lemmings (a little like a gopher). They feed on the tundra’s plants and are food for the larger mammals, the smaller ones like the Arctic fox, and birds. |

| About 80 kinds of birds can be seen in the Arctic. But most birds are here for the summer only. They come here to nest and breed, then head south. The most amazing is the Arctic Tern. It follows the sun, year ‘round, so this bird is built to fly. It breeds and gives birth in the summer of the far north, then flies 12,000 miles to the Antarctic for the summer down south. In its lifetime, an Arctic Tern may fly 480,000 miles (that’s farther than going to the moon and back!). The snowy owl, eider duck, ptarmigan, and raven live in the Arctic all year. |

The Arctic Tern is the world’s longest migratory. It sees more sunlight than any animal on the earth. |

The busy bee, even in the Arctic! |

Over 600 species of insects live in the Arctic. Mosquitoes are the most common insects. They suck the blood of larger animals. Their larva hatch and grow in pools of melted snow. Bumblebees pollinate the tundra flowers that bloom in late summer. One could find butterflies, beetles, and flies, too. |

| Over 500 species of wildflowers bloom every summer. Moss and lichen grow in and around the rocks and berries ripen in the later summer, providing food for mammals and birds. The most amazing plant is the willow tree. The branches of this tree grow along the ground to protect it from the strong, cold winds. It has learned to live with poor soil, frozen ground, and only the water from summertime melting. A trunk the size of your thumb may show 200 growth rings under a microscope. |

Plants, rocks, and moss collected on Ellesmere Island. |

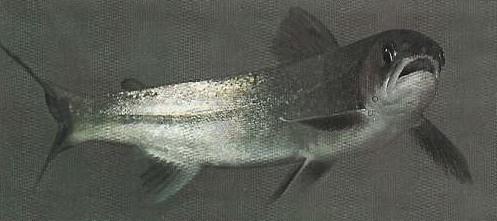

A freshwater fish, the char. |

About twenty kinds of fish live in the salt and freshwaters. Salmon, lake trout, and Arctic char live in the lakes of the tundra. I still have not seen the amazing mammals of the sea like the whales, seals, walrus, and narwhal, but they are out there, too; more about them another day. |

|

| All photos except those from Ellesmere Island courtesy of Wildlife Explorer, International Masters Publishers, 1998. |

|