Ride of a lifetime

Robert McCarthy |

|

This heading could pertain to this entire research cruise; the scenery and breaking through ice on the Healy is amazing. But here, I’m talking about the “helo” ride! The helo is short for helicopter. The Healy is equipped with 2 of them, and they proved to be invaluable. They flew into Pond Inlet to pick up some cables for the ADCP, and without them, this cruise (for the most part) would have been a failure. There is other extremely good and important research taking place on this cruise, but $1.3 million dollars was spent on getting precise and accurate data of the flow through Nares Straight with the bottom ADCP moorings. Without those cables, they wouldn’t have been deployed. All I can say is, "Thanks to the helo operation crew"! |

| But that’s not all they do. They routinely fly north to scout out the ice cover, so the ship can navigate around some pack ice if permitted. Their most dangerous and important duty is sea-rescue. Each helicopter is equipped with a winch to save a person in the water. But today and on August 3rd, they flew to scout out possible locations to send the diving team looking for clams. Today Gerhard Behrens flew, and on August 3rd, I had my first helicopter flight. Not just any helicopter flight mind you, but one off the back of a moving ship in the Kennedy Channel north of 80 degrees latitude. That’s a "ride of a lifetime"! |

|

|

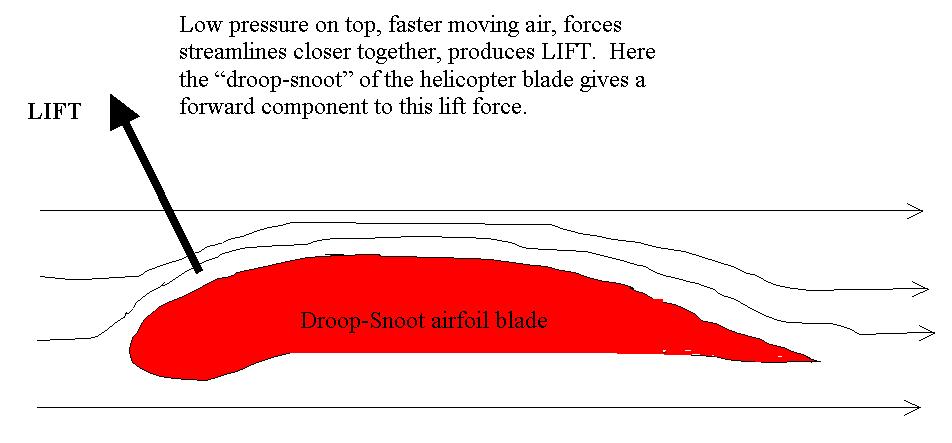

So how does a helicopter fly? Bernoulli has the answer. The helo has 4 rotating blades, each shaped like an airfoil with a length of about 20 feet. |

|

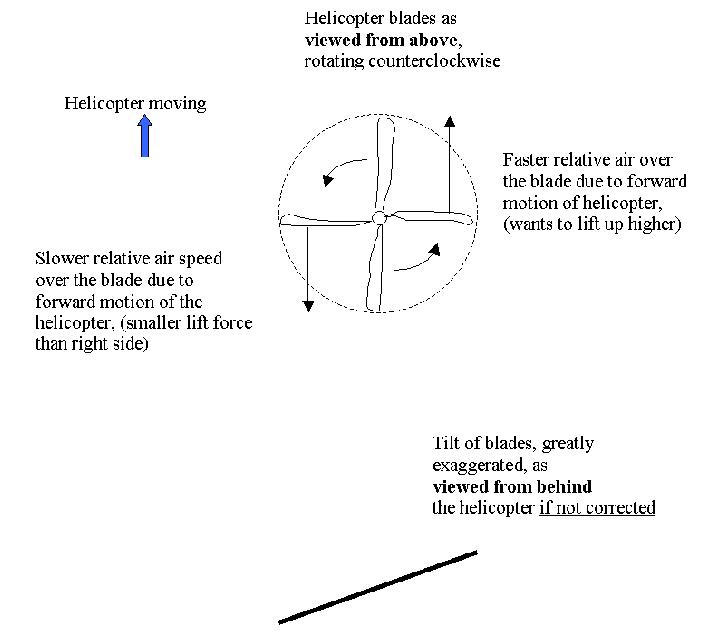

| These rotate at 350 revolutions per minute (rpm’s). So how fast is the linear velocity at the tips of these blades? Take the radius of the circular motion and multiply it with the rotational velocity in radians per second. This gives me about 220 m/s, or roughly 500 mph. These blades rotate counterclockwise, and without lift correction would be tilted slightly from lower left to upper right if viewed from behind. This is because the blade on the right (as viewed from above) is moving relative to the air faster than the blade on the left. Bernoulli found that the faster moving fluid has a lesser pressure. So the right blade would be lifted up more than the left blade if it weren’t for the slightly different pitch of the blades as they rotate. See schematic for why the blades want to tilt. |

|

|

| Also, the maximum lift is positioned closer to the end that’s rotating the fastest, and tapers off to hardly any lift near the central rotating shaft. The rear blades, rotating vertically, help stabilize the helicopter, and counteract the rotational torque of the top blades. |

|

The maximum weight of the helicopter is 9200 lbs., which includes maximum fuel capacity of 1800 lbs. They burn about 600 lbs of fuel per hour, and can travel a maximum horizontal distance of 120 km one way. The cruising speed is about 165 knots, roughly 190 mph. It was quite a ride, one I’ll never forget. Thanks to the pilots, Lt. Damon Williams and Lt. Gary Naus for my safe and smooth flight, and everybody else who sees to it that those flights go off without a hitch. Thanks, “Helo-ops”! |

Chance of a lifetime

Gerhard Behrens |

| Sometimes, lots of hard work can really pay off. If you read every night, you will become a good reader: you learn to read any word and you understand what you read. If you shoot hoops, work on dribbling, and practice teamwork, you can become a good basketball player. |

Getting the chance of a lifetime. |

The rugged mountains of Ellesmere Island reflected in the calm waters of Kennedy Channel. |

But sometimes, something great happens…just because. You don’t deserve it, you didn’t earn it, you just get lucky and the chance of a lifetime stares you in the face. |

| This whole trip is one of those times. Cruising these Arctic waters with the world’s leading scientists and a first rate Coast Guard crew is a chance of a lifetime. This morning, my luck took one more turn for the better. I was able to ride in a helicopter to help scout out mooring sites and clam sites on Ellesmere Island. |

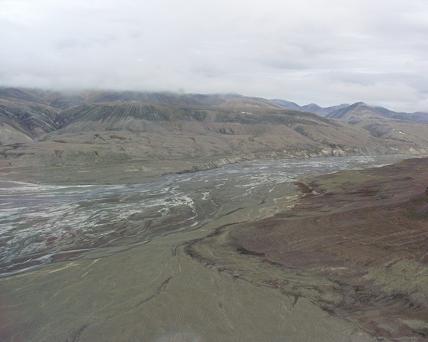

The mountains and river valleys are barren, but beautiful. |

This broad river valley was a lunch spot for 4 muskoxen. |

Everything that happened is a great memory. We sat in the helo for close to 10 minutes while the pilots and ground crew checked and rechecked the helo: engines, blades, computers, pressure, fuel tanks, radar…check, check, check, check, check, and recheck. I always wondered why it took so long for the helo to lift off. Now I was glad for each check and I didn’t care how long it took before we began! |

| Up in the air, I was thrilled with the view of our ship and the Kennedy Channel. For the last 17 days, I was part of a ship that dropped equipment into the water and hauled up samples or data. Now, the ship became part of the water, and the water was part of a big channel that connected the Arctic Ocean and Baffin Bay and the North Atlantic Ocean. The helo had given me a new set of eyes on our mission. |

A member of tie-down crew checks the helo deck for safety. |

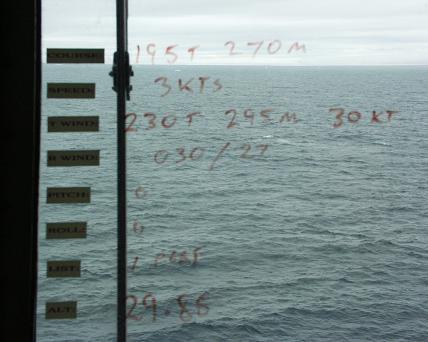

Officers in the flight tower record flight conditions right on the window. |

I was amazed at the smooth and agile flight of the helo. We took sharp, but graceful turns. We dropped quickly and easily from 500 feet to 75 feet above a gravel beach. The helo allowed us to look hard for good places to put in a mooring and find clams. We also enjoyed the views of beautiful cliffs and the desolate river valleys of rugged Ellesmere Island. A small herd of 4 muskoxen reminded us that there is life among all the rock. |

| We landed on the ship and I was thankful for the skilled pilots, Greg Matyas and Damon Williams. But there is a huge team that puts a helo up and lands it: mechanics who keep it running, seamen who put fuel in, firemen who stand watch, more seamen who push the helo to its deck and handle its tie-downs, safety technicians who provide a weather forecast, and the officers who work in the flight control room. |

Landing Signal Officer (LSO) guides the helo and gives commands on the helo deck. |

The tie-down crew enters to secure the helo. |

Maybe the luckiest thing about this flight was the lesson I learned, again, about the importance of teamwork. |

Securing the helo to the deck. |

Preparing helo to enter the hangar. Mechanics, Technicians, and Pilots help out. |

A team must push the helo in and out of the hangar. |

Support crew clothing: Silver fire suits; red for fire team; purple for fueling team; yellow for the LSO; Missing are the blue vests for the tie-down and pushing team (Helo Traversing Detail). |